- Play Title: Not I

- Author: Samuel Beckett

- First performed: 1972

- Page count: 8

Summary

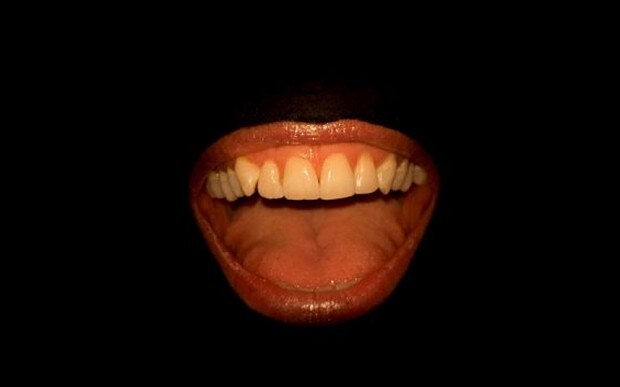

On stage, there is a mouth with a spotlight shining on it. No face is visible, nor body. All else is dark, although a mysterious, lean figure looks on from the corner. The mouth begins to mumble at first, then it spews forth words at a frenetic pace. Saliva slithers across the glistening teeth as the lips contort to produce each distinct syllable in a rapid-fire delivery of an extended monologue. This is what a performance of Samuel Beckett’s Not I looks like.

The story itself is inconclusive, disjointed, and impressionistic. A narrator (mouth) delivers an amalgamation of the experiences of ‘she.’ First, there is a brief biography of an unwanted baby girl. She is now aged 70. One April day in a field, she loses her senses and becomes almost fully insentient due to … maybe an epiphany, mental breakdown, or possibly a medical reason. However, consciousness persists and suddenly, involuntarily, she begins to speak – reams and reams of words. She has been a devout, lifelong mute who now experiences a purge of jabber. Memories pop up, like crying in Croker’s acre that one time; shopping with her old, black shopping bag; trying to talk and feeling shame at others’ reactions; and being in court – “Guilty or not guilty” (Beckett 381). She remains face down in the field, wondering if it is God’s work, glad that it does not hurt, but not really knowing at all.

The theme of Not I is not readily apparent, but it appears that Beckett captures a woman’s crisis, a fracture from her old self, a sudden unexpected break!

Ways to access the text: watching /reading

This is foremost a performance piece, so I would recommend watching the BBC recording of Billie Whitelaw’s version. This is free to view on YouTube, entitled “[1973] “Not I” (Samuel Beckett).” There are various other versions available online, but Whitelaw was one of Beckett’s favourite actresses, so her rendition conforms to his exacting standards.

The text of the play may be found in Samuel Beckett: The Complete Dramatic Works. The Internet Archive currently carries a copy of this text.

Why watch/read Not I?

Watching Whitelaw’s [mouth’s] performance of Not I is quite riveting. The energy is palpable, and it fizzes through the words in an almost manic, neurotic style. Her diction is precise, yet she wrangles, at times, with the demands of enunciation at meteoric speed. The performance becomes (almost) equally demanding for an audience who must grasp enough of the assorted words being flung forth so that a comprehensive story may be assembled. The set design, the focus on just a mouth centre stage, and the odd, silent figure all make for an intriguing theatrical experience. Beckett’s play is over fifty years old, but it is still innovative and demanding. Not I is a consummate aural assault, which jolts the modern listener out of their Netflix-induced mental lethargy!

Post-reading discussion/interpretation

Enlightenment – The Unexpected Counterweight

When Billie Whitelaw first read the script of Not I, she felt it was about the ‘inner scream’ (YouTube). According to her, Beckett had not only described a state of mind but had managed to put it on stage too. The entity on stage is named “She,” and the voice comes from Mouth (hers presumably, but that is not stated, or certain). The spectacle on show is a woman in a sudden crisis, however, no specific precipitating event is named. What is revealed in her backstory is a long and mostly uneventful life, which has been utterly loveless in nature. Her reported habit of silence could be a case of (s)elective mutism, especially given her up-until-now preference never to speak. At last, a clue! What existed before the spectacle of the rampaging mouth? Self-enforced silence, which is most commonly seen in children but rarely in adults, is typically characteristic of people with high levels of social anxiety, trauma (PTSD), depression, or some toxic mix of the aforementioned comorbidities. The backstory is undoubtedly one of pain. What is and has been absent is not just an authoritative I, but also the essential, foundational love of a parent (either), grandparent, lover, or friend. She has never materialised into a whole person since no one ever saw her as special, lovable, or unique. She chiefly existed, never lived. Beyond the circumstantial handicap of being abandoned as an infant, one may speculate if she has an intellectual or physical disability. Her voice is odd, even to her – why? Is she partially hearing, which causes her voice to sound strange? A mental handicap could explain her frequent open-mouthed pose. She could be on the autistic spectrum. One such ‘flaw’ may also account for her abandoned status – beginning with her parents. In her disadvantaged life/body/disposition, she has accumulated a vast store of rejections, humiliations, and deep hurts. Stoically, silently, she has lived on. Although partially speculative, this is a guiding outline of the figure on stage.

Beckett sets this figure before us, and we are mesmerised by her outcry. However, it is a conundrum because her 70 years of self-enforced silence are suddenly counterweighted by an extraordinary outburst. The moment is unique and gloriously relevant – maybe even mystical. This brief essay aims to untangle, or possibly further tangle the story into comprehensibility.

Like in the case of a dammed river, the pressure mounts and the barrier is tortuously strained. The burst of language that constitutes the performance in Not I is a long overdue release. The words are crucially involuntary and unfiltered – an electric, eclectic feed from brain to lips. The verbal purge is disjointed and sometimes utterly confusing due to the lack of regular syntax. “She” is uncharacteristically energised. When actress Jessica Tandy asked Beckett for pointers before first performing Not I in New York, he said “I’m not unduly concerned with intelligibility. I want the piece to work on the nerves of the audience” (Gillette 288). The piece needs to affect an audience in the moment, to grab them blithely unawares. Brenda O’Connell states that “the image of Mouth, who is – or who is speaking for – a seventy-year-old ‘hag already’, closely resembles a vagina, a profoundly abject and vulnerable symbol of the feminine” (96). In contrast, “James Knowlson and John Pilling suggest that Mouth’s outpourings are excremental” (O’Connell, 106). If ‘she’ has derived no pleasure from sex, as stated, then maybe she is indeed performing a type of mental defecation. The ills of her mind, the unkind memories, need to be purged violently and without any prior thought.

Beckett’s choice of pronoun is thought-provoking too. One understands it as a first-person narrative but it’s Not I, apparently, and not You either, but She. Why is there such a chasm between the speaker and her own intensely personal story? The space between I and She is instrumental because She is quickly visualised by an audience as the limp-bodied 70-year-old woman lying face down in a field on an April morning, whereas I is the still-active, hidden speaker – the mind. This stark depiction of Cartesian dualism, this conspicuous split, facilitates a more rapid interpretation. I is the mind, while She is just the material body – and You is the silent auditor in the corner of the stage (judging?). Enoch Brater has analysed the play’s use of pronouns and gives the following perspective.

“The staging of the play suggests both a religious confessional – Auditor’s attentive cowled figure, the mouth pouring out words while the rest of the face remains hidden in the darkness– and also a literally dislocated personality: an old woman listening to herself, yet unable to accept that what she hears, what she says, refers to her.”

(Brater 193)

The woman’s body falls away, figuratively. This identity crisis may be explained by her old age, the absence of a sense of self, or a catastrophic lack of self-esteem. The rarefied conditions made possible by the stage production exhibit an extraordinary detachment, which is perfectly reflective of the woman’s emotional state.

The play’s monologue strives for immediate effect, not coherence. The monologue may be the ephemeral materialisation of a revenge rant. This splurge of words is her only means of balancing out the ancient wrongs done to her – a counterweight of sorts. She gets her say via an anonymous mouth, and, therefore, it is uncensored and unapologetic. Mouth insists upon deliberate one-way communication; She has no receptive ears for an anticipated response, no eyes to take in the disagreeable or confused looks, and no hands to gesture in appeasement or understanding. She is armoured against all our potential responses. For those suffering from selective mutism, as she likely does, “the expectation to talk to certain people triggers a freeze response with feelings of anxiety and panic, and talking is impossible” (NHS). This barrier is now removed. There is only unrelenting sound – to which the audience is subjected. The subjugated suddenly morphs into the subjugator. Nonetheless, this is the occasion of a breaking point, hers. Her unfolding story is conspicuously barren, with not a whit of joy or satisfaction. The moment of now is seemingly the moment of her judgment or death, and her life is summed up like one who fears to pay the price yet is impelled to tell her story.

In contrast to viewing the scene as one of an unseemly mental breakdown, maybe she is having an epiphany. There are her repeated references to God’s love, punishment, and forgiveness along with the strange, dim light, which is not seen with the eyes. Two reference points immediately come to mind. First, the philosophy of Quietism: “a doctrine of Christian spirituality that, in general, holds that perfection consists in passivity (quiet) of the soul, in the suppression of human effort so that divine action may have full play” (Britannica). Beckett was quite familiar with this philosophy (Wimbush 204). Additionally, “quietism encourages human beings to recognise their worthlessness, impotence, and ignorance, and to submit humbly before God” (Wimbush 204); this matches her marked passivity and total silence throughout a long life. The second reference point is St. John of the Cross’s poem entitled “The Dark Night of the Soul.” The phrase is shorthand for a crisis of religious faith but also refers to the secular idea of a person’s lowest point. In the poem, this Christian mystic refers to a metaphorical guiding light that leads him to God, and he tells of how all his senses were suspended at that moment. The similarity of her experience in the field, as she thinks of God, is too closely aligned with accounts of Christian mystics to be entirely coincidental.

However, her search for an answer never finds a conclusion – “what she was trying … what to try … no matter … keep on” (Beckett 383). The voice, which an audience must hear to make the performance viable in a theatre setting, could represent a silent scream inside her own skull – a wordy barrage that runs rampant through her brain in an ecstasy of hoped-for revelation. If her silence has always had value because it connects her with her Maker, then this moment of panic could indeed be religious ecstasy leading to enlightenment. Alfred Barratt Brown wrote about the dark night of the soul, explaining that, “The “mystic death”-the crucifixion and burial of the old self – is followed by the attainment of a “resurrection” personality” (487). An alternative and quite sobering, literal view is that an unloved, 70-year-old mute lies face down in a field. Beckett’s play ends with the search for her life’s meaning still ongoing, but tantalizingly close to revealing all. As an audience, we have had our mechanism of thought engaged, and challenged, and we try to extrapolate a meaning that explains her struggle, and maybe ours too.

Works Cited

Beckett, Samuel. “Not I.” Samuel Beckett: The Complete Dramatic Works, Faber and Faber Limited, 1990, pp. 373-384.

Brater, Enoch. “The ‘I’ in Beckett’s Not I.” Twentieth Century Literature, vol. 20, no. 3, 1974, pp. 189–200. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/440518.

Brown, A. Barratt. “The Dark Night of the Soul.” The Journal of Religion, vol. 3, no. 5, 1923, pp. 476–88. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1195685.

Gillette, Kyle. “Zen and the Art of Self-Negation in Samuel Beckett’s ‘Not I.’” Comparative Drama, vol. 46, no. 3, 2012, pp. 283–302. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23526350.

O’Connell, Brenda. “Samuel Beckett’s ‘Hysterical Old Hags’: The Sexual Politics of Female Ageing in All That Fall and Not I.” Nordic Irish Studies, vol. 17, no. 1, 2018, pp. 95–112. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26657500.

“Quietism.” Britannica, http://www.britannica.com/topic/Quietism.

“Selective mutism.” NHS, http://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/selective-mutism.

St. John of the Cross. “The Dark Night of the Soul.” Poetry Foundation, http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/157984/the-dark-night-of-the-soul

WIMBUSH, ANDY. “Humility, Self-Awareness, and Religious Ambivalence: Another Look at Beckett’s ‘Humanistic Quietism.’” Journal of Beckett Studies, vol. 23, no. 2, 2014, pp. 202–21. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26471156.