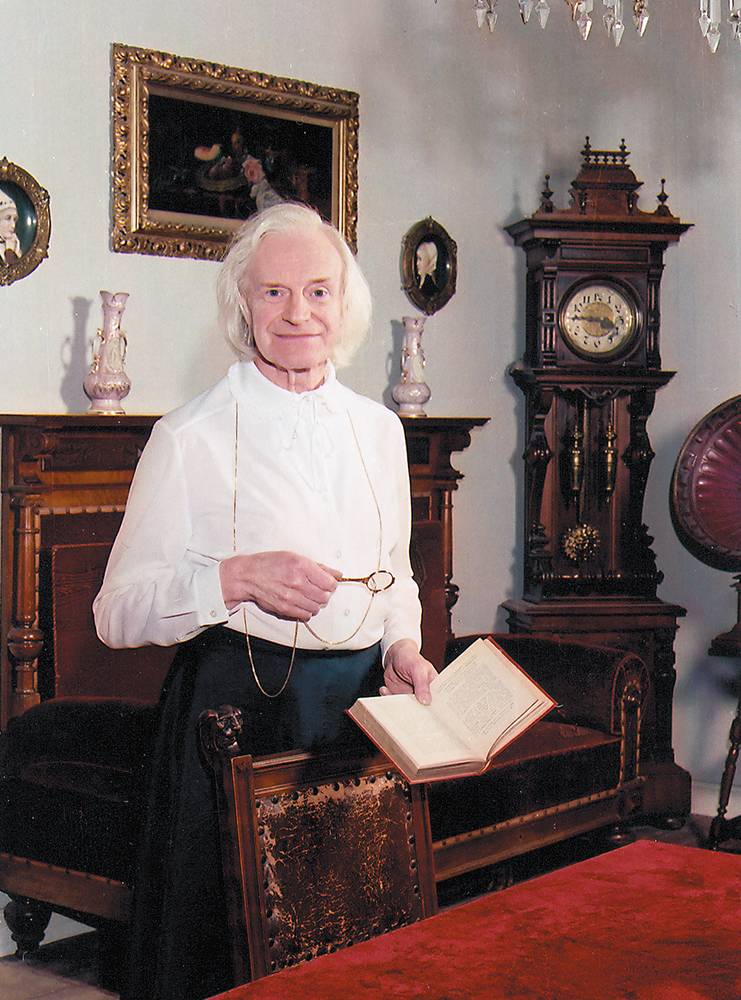

Charlotte von Mahlsdorf at home in the Gründerzeitmuseum.

- Play Title: I Am My Own Wife

- Author: Doug Wright

- First performed: 2003

- Page count: 83

Summary

I Am My Own Wife (2004) is Doug Wright’s account of Charlotte von Mahlsdorf’s extraordinary life. Wright first met and interviewed von Mahlsdorf in 1993 and was fascinated by this transvestite from the former East Germany (DDR). Born in 1928 and named Lothar Berfelde, Charlotte was her assumed name. She had an eventful life, which included cross-dressing, patricide, establishing a museum in her house, working as an informer for the Stasi, and releasing her own book in 1992 entitled “Ich bin meine eigene Frau” (I Am My Own Woman). Von Mahlsdorf died in 2002, prior to the release of Wright’s play. She was already a famous figure in Germany.

Wright gave the following subtitle to his work – “Studies for a Play About the Life of Charlotte von Mahlsdorf.” Indeed, the script is a perfectly assembled hodgepodge of Charlotte’s reminiscences, various letters, accounts of TV interviews, and media coverage; the play’s author even appears as a character. The completed play is a testament to the difficult but ultimately successful construction of a story. Wright believed he had found “a bone fide gay hero” (Wright 89), but Charlotte was a real person and not merely a good story. The central themes of the work include identity, truth, and narratology.

Ways to access the text: reading

I used the Everand digital library to get access to this playscript. Members pay a subscription, but it is possible to use the 30-day trial period to read the text. There is no audiobook or filmed version of the play, to my knowledge.

If you are interested in Charlotte von Mahlsdorf’s story, then various other works give good insights. For example, the movie entitled ‘Ich bin meine eigene Frau’ is available on the website Rarefilmm.com. This film has a running time of 1hr. and 31 mins., and there are English subtitles.

Mahlsdorf’s autobiography, which is entitled I Am My Own Woman, is available to read online via the Open Library.

Why read I Am My Own Wife?

Wright’s play gives an account of a genderqueer individual’s life. Lothar was born biologically male but later assumed the name Charlotte to reflect her feminine side.

“In my soul, I feel like a woman. That does not mean, however, that I am self-conscious about my male sexual organs. I am not a transsexual.”

(Mahlsdorf 47)

Instead, Wright presents a somewhat unreachable central character, and his own attempts to understand and write about her become the core subject matter of the play. I would highly recommend this play to anyone interested in how real-life stories can utterly change when told by different people. Charlotte remains an engrossing central figure, but the play is not the simple retelling of her life story, as one might expect.

Post-reading discussion/interpretation

An Unnecessarily Problematic Metanarrative

Based on certain interests and expectations, one goes to a theatre performance or reads a playscript. I Am My Own Wife is the story of a real-life figure named Charlotte von Mahlsdorf aka Lothar Berfelde. Therefore, one likely expects an LGBTQIA+ (friendly) story. However, Wright immediately upsets one’s comfortable expectations with the work’s odd subtitle – “Studies for a play about ….” Is this a niche, academic book about dramaturgy or an entertaining, theatrical retelling of a distinctive life story? The answer is the latter, luckily, but the author has already implanted a crucial doubt in a reader’s mind regarding the complexity of the central subject. The subtitle exudes the idea of something laboured and intellectual. Back in 1992, von Mahlsdorf released her own book in German, and the English translation was released in 1995. The subtitle of that autobiography is “The Outlaw Life of Charlotte von Mahlsdorf, Berlin’s Most Distinguished Transvestite.” Although far more informative, this subtitle is also problematic since the word transvestite is now considered outdated and is even listed as a derogatory term in most modern dictionaries. The book’s main title is I Am My Own Woman (Ich bin meine eigene Frau). Jean Hollander, the book’s translator, points out that the original German title may validly be translated as I Am My Own Woman or I Am My Own Wife (Translator’s Note). These almost overlapping titles quickly begin to confuse. This brings one to the crux of the matter on just the cover page; has Wright simply retold Charlotte’s story under a practically identical title, or has he made it his own? If he has made it his own, then what is the trade-off, if any? Is the play a straightforward hagiography, a balanced account, or what may colloquially be called a hatchet job? This essay aims to explore why, and how, Wright takes control of Charlotte’s story (which he does) and the unexpected repercussions of this decision.

The title of von Mahlsdorf’s book versus Wright’s play title is a quietly significant point. In 1992, von Mahlsdorf’s book was quickly followed by the movie version entitled Ich bin meine eigene Frau, which was directed by Rosa von Praunheim. The book and film carry identical titles in German and English, indicating the film’s loyalty to the autobiographical story. Furthermore, Charlotte stars in the movie as herself, as a kind of omniscient narrator. For a male transvestite who feels they are really a woman, the title (My Own Woman) encapsulates the idea of both genders being comfortably accommodated in one physical body. In contrast, Wright’s chosen translation, though also technically correct, emphasises the fact that Charlotte never married – I Am My Own Wife. Indeed, these are the words that the then-40-year-old Charlotte used to explain to her mother why she would never need to get married (Mahlsdorf 175). Wright’s title subtly draws attention to the fact that Mahlsdorf is attracted to men and will never marry. To be one’s own wife communicates that women do not have a role in Charlotte/Lothar’s life that he cannot fill himself – this has obvious sexual implications too. Charlotte speaks of her natural passivity on two occasions when referring to sex and BDSM (Mahlsdorf 105,115). For Wright, Charlotte is primarily a gay icon, a gay man, whereas her own story’s title lends itself far more to a fruitfully troublesome contemplation of gender. Wright diverges from Charlotte’s viewpoint for various reasons, which probably include artistic licence, an independent perspective, and the importance of novelty in an already well-known story. However, it is mainly because Wright has doubts about the reliability of Charlotte’s story. The play title is not just about whimsical differences in translations, it’s the first hairline crack that appears in the relationship between writer and subject.

The playwright presents an on-stage scenario where he becomes gradually more distanced from Charlotte due to his own slowly emerging doubts regarding her credibility. Nevertheless, a German-language autobiography of Charlotte and a movie of her life with English subtitles were available from 1992 (before Wright first met Charlotte). Referencing her book, one certainly finds some incredible stories. For instance, Charlotte states that her mother and Aunt Luise readily accepted her non-conforming gender identity, and her uncle once bought her an item of women’s clothing, a coat (Mahlsdorf 16,44,46). Apart from a Nazi father, she presents an exceptionally enlightened, tolerant family. There are also stories of a housemaid who beat Lothar/Charlotte because he did not want to wear a boy’s First Communion outfit, he wanted a dress, and a shop assistant who was irritated by his attraction to girls’ fashions. Although first presented as old-fashioned, both women subsequently agreed that Lothar looked far better in female garb (46). Such stories soon begin to stretch the credulity of her readership to the limit, even abuse it. Furthermore, Charlotte says she regularly cross-dressed in public from 1945 onwards, but the people of her neighbourhood took little if any notice (102). Apart from Charlotte’s Pollyanna attitude, which is perfectly acceptable, she appears to have pinkwashed her entire personal history. When checked against the historical realities of Germany in the 1930s and 40s, including the anti-gay law known as Paragraph 175, Charlotte’s accounts of events provided in the autobiography are just too incredible, aka not believable. All this information was in the public realm before Wright commenced interviewing Charlotte in 1993. The timeline becomes more relevant as one further scrutinizes the play.

The unreliability of Charlotte’s story was not to be Wright’s only dilemma. Michael R Schiavi makes a fundamental point about Wright’s extensive interactions with Charlotte – “Charlotte’s patricide and her betrayal of friend Alfred Kirschner to the Stasi remain mysterious even to Wright himself during his lengthy interviews of Charlotte” (196). As Charlotte’s newest biographer, Wright is strangely unable to elicit any fresh information about the key events of his subject’s life. Charlotte’s story remains honed, polished, and impermeable, even after the shocking revelations of the Stasi files. Wright is left with the option of presenting Charlotte’s story (as is) to the theatre world – a nice addition to the autobiography and film – or he can somehow remove himself from the role of loyal biographer. Schiavi explains that as a consequence of Wright’s predicament and subsequent artistic decisions: “the principal subject of Wife is less the murky life of its protagonist than the construction and reception of biodramatic truth” (196). This may explain why issues like Charlotte’s sexuality and gender identity, issues at the core of her personality, become oddly overshadowed. Interestingly, Schiavi questions if Wright’s choice of subject matter is inherently problematical from the outset – “Is it hopelessly naive to seek verisimilitude in the staging of a real historic figure, particularly one possessing multiple identity categories (transvestite, homosexual, murderer), under ceaseless social siege during her life?” (196). Charlotte is a practised storyteller and she competently, even if slightly conspicuously, defends her own version of events in her book and as the on-screen advisor in von Praunheim’s movie (198, 201). It is Schiavi’s view that Charlotte’s insistence on denying or ignoring her stories’ inconsistencies is actually a bonus for the play.

“The play’s exceedingly dubious protagonist keeps audiences engaged precisely because she forces them to reexamine the trust typically accorded biodrama, a theatrical form predicated on the dubious revelation of truth.”

(Schiavi 197)

Schiavi’s astute insights prompt an obvious question; at what point did Wright comprehend the unreliability of Charlotte’s story? I contend that the playwright most likely knew this before commencing his project, whereas the play presents Wright’s qualms about the project as occurring much later. One hypothesis is that Wright found an amazing, gay-positive story and only when Charlotte’s otherwise harmless, fantasist leanings morphed into a cover-up of Stasi collaboration did the playwright distance himself from his subject by using quite technical, dramaturgical techniques. In other words, the perfect gay story went bad and necessitated a quite different approach. This reading of the situation is based on Charlotte’s book and other information that Wright had access to in advance of agreeing to write her story. The author also had the assistance of German-speaking John Wright who had recommended the story in the first place. Presenting a timeline on stage is complex, and a play need not stick to real-life sequential developments. However, in a biographical play where a timeline and credibility dovetail, that’s an issue. The point here is not to catch Wright out, but rather to spotlight the fact that authors take ownership of stories, they are not just curators of them. When a story fails to deliver upon the initial expectations of a writer, then it is often reshaped to meet new ends.

To use a literary term, Wright chose to present Charlotte as an unreliable narrator in I Am My Own Wife. This is an unusual choice for a biographical story. M. H. Abrams explains the implications of having an unreliable narrator in a text, as follows.

“We ordinarily accept what a narrator tells us as authoritative. The fallible or unreliable narrator, on the other hand, is one whose perception, interpretation, and evaluation of the matters he or she narrates do not coincide with the opinions and norms implied by the author, which the author expects the alert reader to share.”

(Abrams 235)

The unspoken alliance between biographer and real-life biographical subject abruptly ends in such a situation. Wright effectively pushes a theatrical version of Charlotte before an audience and invites critiques. Greta Olson further explains the term unreliable narrator with the aid of Wayne Booth’s well-known writings on this topic.

“Booth understands narrator unreliability to be a function of irony. Irony provides the formal means by which distance is created between the views, actions, and voice of the unreliable narrator and those of the implied author.”

(Olson 94; emphasis added)

The playwright uses subtle techniques to create this distance between himself and Charlotte. Despite these deft touches, it is helpful to keep Olson’s quote in mind and appreciate that Charlotte is being treated ironically. For instance, why is it important for an audience to know that the reputable journalist John Marks thinks that Charlotte’s story is probably unsuitable for his mainstream media organisation since it is “too extreme” (Wright 9)? Why does Doug, as a character in the play, tell Charlotte “It seems to me you’re an impossibility. You shouldn’t even exist” (15)? This comment refers to the fact that Charlotte has somehow survived, practically unscathed, through Nazism and Communism. Other comments are crueller since they undermine Charlotte’s stated identity. For instance, during one of their initial meetings, Doug gives an aside to the audience, saying, “Doesn’t look like a drag queen at all. No makeup … her hands are big, and thick. The hands of a woodworker. A craftsman. Definitely a man’s hands” (20). This comment in particular invites an audience to view Charlotte as a fake since her stated gender is dissonant with her appearance. Later in the play, Charlotte’s credibility is ridiculed regarding her explanation of her interaction with the Stasi and the subsequent effect on Alfred Kirschner. John Marks exclaims that Charlotte’s account of these events is “one helluva story” (60). In other scenes, such as ‘Editorials: A Phantasmagoria’ and ‘Diagnosis,’ the audience witnesses both the international media’s rough treatment of Charlotte, followed by a psychiatrist’s damning diagnosis. The inclusion of such details is a form of death by a thousand cuts for the central character. Olson explains that “unreliable narrators are consistently unreliable” (95), so one’s trust cannot be restored in them. Charlotte cannot redeem herself within the matrix of the play.

However, the unreliable narrator is just one half of the equation – what about the implied author that Olson references? Brian Richardson explains the implied author as follows – “This figure is not the biographical individual who composed a given work, but an idealized persona who seems to stand between the author and the text” (206). One cannot communicate with that real author via the text since our allowed impression is only of an implied author. Furthermore, the Doug who appears as a character in the play is a construct designed by the real author. Having first outlined the degrees of separation, it is possible to assume that the Doug character representing the author is closely, if not perfectly, aligned with the views of the implied author. The Doug character is a sympathetic and engaging figure. Much like Charlotte, his story may be true, or not. For example, Doug initially presents himself as an eager, enthusiastic theatrical biographer of Charlotte. He is a gay kid from the American Bible Belt (Wright 15) who begins to see Charlotte not as a museum curator but as an actual gay museum piece herself (32). He believes that Charlotte’s fantastic life merits a play (89), and, on a personal level, he credits her with teaching him gay history he never knew (23), such as Magnus Hirschfeld’s writings. The Doug we meet is reverently shy around Charlotte at first (20) and is crushed by Charlotte’s later confirmation of Stasi collaboration (41). This figure, who is an amalgam of Doug as character and implied author, is somewhat of a mirage too.

The Doug character narrates and thereby directs much of Charlotte’s story. Albeit an unconventional approach, Richardson argues that a narratorial point of view is as applicable to drama as it is to fiction, and that “narration is a basic element of the playwright’s technique” (194). He goes on to explain that the narrator is “the speaker or consciousness that frames, relates, or engenders the actions of the characters of a play” (194). As such, the on-stage Doug has the authority to put a particular spin on the entire story. For instance, Charlotte is presented as eccentric and flaky, whereas Doug is earnest and naïve. In the scene named ‘Abdication,’ Doug confesses to John that despite the play’s numerous problems, he “need[s] to believe in her [Charlotte’s] stories as much as she does! (Wright 76). This reminds one of the entrancing authority Charlotte exuded when Doug and John first went to the museum in 1992. Doug described how they and the other visitors were “huddled together like schoolchildren” (12) while listening to their transvestite guide. One may contrast that scene with an alternative impression one gets of Doug Wright in a 2005 interview with Saviana Stanescu. Wright describes Charlotte and the play as follows.

“I’d call my play a “portrait of an enigma.” I was tantalized by the prospect of trying to craft a character study of someone so slippery, someone who, to a great degree, invented herself. How do you dramatize contradiction in a way that adds up to some singular, ineffable truth? That, I think, was my task.”

(Stanescu 102; emphasis added)

This is the real-life, cerebral playwright, not the awe-struck biographer whom one sees on stage (the Doug character). Wright explains to Stanescu that he “become[s] their [the audience’s] tour guide through Charlotte’s foreign and occasionally exotic world” (Stanescu 101). This is a disputable point. Wright does indeed provide the facts of Charlotte’s life; but, as already explored, they are presented in a noticeably biased fashion. The various techniques that Wright employs to outline his characters will ultimately guide our reception of them.

If I Am My Own Wife is a purely biographical play, then how are all these theatrical sleights of hand even possible? Drama is conventionally viewed as a mimetic genre, namely a genre where reality is imitated in art. How, then, does Charlotte’s life story get turned upside down? One may helpfully introduce the term autofiction to illuminate this point.

“When Serge Doubrovsky coined the term “autofiction” in relation to his 1977 novel Fils, he defined it, rather paradoxically, as “Fiction, of strictly real events and facts.”’

(Hansen 47)

Per Krogh Hansen references the work of Gérard Genette when explaining that “all cases in which an author of fiction includes his own person (or a character with the same name as the author) in his fictional story should be considered autofiction” (49). Wright’s play qualifies as autofiction because Doug is both the external author and an internal play character. However, can one categorize Charlotte’s story as a work of fiction? The answer is yes when one considers Doubrovsky’s definition again (fiction of real events) plus Wright’s ongoing suspicions about Charlotte’s story in its entirety. By initially presenting Charlotte as an unreliable narrator, Wright has already secretly stamped the work with the cautionary label of fiction. Classifying Wright’s play as autofiction solves one riddle because “What autofiction does is quite radical in the sense that instead of demarcating fiction from reality it blurs the border” (Hansen 49). Thus, neither Charlotte nor Doug, as presented in the play, may accurately correspond to their real-life counterparts. This all seems unnecessarily confusing until one takes the concept of personal truth into account – “autobiographical theory has repeatedly shown that “subjective truth is far more important to memoir than literal truth […] because it is crucial to the autobiographer’s ability to give shape and meaning to experience” (Hansen 54). As Wright explained to Stanescu during their interview, “the journey of the play might actually be the journey I took with her [Charlotte]” (Stanescu 106). Consequently, one is witnessing a protracted battle between two personal truths – Doug’s journey through the events of Charlotte’s life. Doug, the idealized version of Wright the author, guides us through Charlotte’s life with the equivalent of an occasional raised eyebrow or sigh of exasperation. The truth becomes blurry indeed.

Terms like unreliable narrator and autofiction are essential to a solid understanding of Wright’s play, yet they open up an assortment of problems too. In the afterword to the play entitled ‘Portrait of an Enigma,’ Wright states, “While I hope the text does justice to the fundamental truths of Charlotte’s singular life, it is not intended as definitive biography” (101). These fundamental truths do not include Charlotte’s patricide nor the definitive reason for Alfred Kirschner’s imprisonment, so these truths are scarce. To make matters worse, David Stromberg explains that “The language of unreliability introduces value judgment … The term “unreliable narrator” was used mainly to relate either to the cognitive abilities or to the moral attitudes of a narrator” (62,61). Since we do not doubt Charlotte’s cognitive abilities (intellect or memory), there must be a moral question at hand. Stromberg writes that the tension that arises when there is an unreliable narrator and an implied author is not a situation that calls for judgment (from an academic standpoint). Yet, Charlotte’s story is purportedly a true story, or at least her truth, so to place a question mark behind that story is an invitation to judge, to denigrate the character on moral grounds. Wright has employed a structural element in his play that fundamentally undermines our belief in Charlotte. This is the one major flaw of the work, but it is a flaw only in the context of a biographical play. Wright expertly glosses over this thorny point in the afterword by deploying doublespeak.

“Dramatic heroines require dimension, the requisite character flaw that renders them human. I urgently needed to include Charlotte’s duplicity; it was the price she paid for living the unequivocal, unapologetic life of a transvestite. To suggest she accomplished something so bold without compromise was to minimize the achievement itself. True iconoclasm always comes at a price.”

(Wright 98)

By blurring the line between fact and fiction in the play, the playwright disenfranchises Charlotte: she loses her authority as the narrator of her own story. Instead, one is left with a figure that could just as easily have been a fictional character; thus, the value of her experience is wholly lost. A vital difference exists between Charlotte’s autobiography and Wright’s play, and that is the presence of an intermediary interpreter (Doug as character/implied author). In factual narratives, the author and narrator are often the same (Hansen 56)..

“This, however, does not rule out the possibility of unreliability. The storyworld is simply not governed by an implied author in these cases, but rather by sensus communis to the extent that readers have a stake in it.”

(Hansen 57)

If one reads Charlotte’s autobiography, then the onus is on the reader alone to accept, question, or disbelieve aspects of the story. It is a kind of perceptive facility that Hansen refers to using the Latin term sensus communis. Since Charlotte is an on-screen advisor in von Praunheim’s film, the same rule applies. A connection like this between the narrator and the audience is quite strong and impactful. Stromberg explains that, in contrast, the implied author “carries the reader with him in judging the narrator” (61). In the play’s afterword, Wright gives an extensive defence of why he included himself as a character, as follows.

“The whole piece [play] could be a rumination on the preservation of history: Who records it and why? What drives its documentation? Is it objective truth, or the personal motive of the historian? When past events are ambiguous, should the historian strive to posit definitive answers or leave uncertainty intact? The only way to pose these questions was through my own inclusion as a character.”

(Wright 93)

Consequently, the play becomes too much the story of its own creation and the man behind that creation. Schiavi writes that “Doug’s centrality to the plot of Wife, which is at least as focused on his study of Charlotte as it is on Charlotte herself, illustrates David Roman’s designation of “queer solo work” as “usually pedagogical’” (204). Charlotte is spotlighted as a sort of oddity, and this is an unfortunate teaching lesson. Interestingly, as a same-sex-attracted cross-dresser in Germany, Charlotte was already a minority within a minority during periods of immense social and political upheaval. Wright’s expertly executed dramaturgical techniques further alienate, or other, a person whose life experiences are already virtually unparalleled. Also, as Stromberg cautions, “doubt about the narrator may spill over into doubt about the narrative” (66). Thus, our faith in the entire story is tragically undermined. Wright told Stanescu that Charlotte’s death in 2000 “was a profound personal loss, but a writer’s liberation. I finally felt like I could tell the whole story, unvarnished” (102). Given the personal bond between the author and the subject, it is difficult to ignore the subtle elements of betrayal in the final depiction of Charlotte in the stage production..

Charlotte von Mahlsdorf (centre) with friends in the Mulackritze.

The fundamental truth of Charlotte’s life is that she identified as having a female soul encased in a male body (Mahlsdorf 47). The subtitle of her own book describes her as a transvestite, so she must have been comfortable with the description; “The term “transvestism” (Transvestitismus) was coined in 1910 by pioneering German sex researcher and political activist Magnus Hirschfeld” (Sutton 336). Charlotte references Hirschfeld’s book on two occasions in her autobiography. First, when her Aunt Luise introduces her to it and later when she uses Hirschfeld’s writings on transvestitism to explain her gender to her mother (Mahlsdorf 44,16). The text became her Bible. Charlotte was already cross-dressing from about age seven and was consequently beaten by her father whenever caught (Mahlsdorf 23-24). She presented as a quite effeminate, little boy, and she explains the lonely feeling of separation that subsequently developed between her and others – “the invisible wall separating me from most people” (25). Hirschfeld’s book was instrumental in allowing Lothar to begin to comprehend her identity and eventually take the name of Charlotte. Katie Sutton explains that as a consequence of Hirschfeld’s writings, “1920s Germany represents a crucial, but often forgotten moment in the history of transgender political organization” (336). Charlotte saw herself as belonging to a group of ‘sexual intermediaries,’ which is a term used by Hirschfeld to describe “men with womanly characteristics and women with manly ones” (463). The term is also referenced in Wright’s play as describing “an utterly natural phenomenon” (Wright 20). Hirschfeld outlines four categories of sexual intermediaries, and the fourth group aligns with transvestitism (479). In essence, Hirschfeld was Charlotte’s first biographer since the sexologist explained her condition in a scientific publication as an objective truth

Thanks to Hirschfeld’s writings and activism, Germany introduced many progressive laws. One judge who was tasked with prosecuting a cross-dresser complained that there was nothing he could do “if German police were so progressive as to issue “transvestite certificates” (Transvestitenscheine) to select individuals to protect them from arrest while cross-dressing in public spaces” (Sutton 335). However, even within the realm of Hirschfeld’s progressive thinking, people like Charlotte were still classified as exceptions. Transvestite certificates were normally issued to heterosexual males, whereas “Male homosexual transvestites were … largely excluded from the terms of 1920s transvestite citizenship” (344). A few specific groups were “perceived as endangering the fragile edifice of respectability,” namely “individuals whose “transvestite” desires went beyond external appearances to encompass a longing for permanent physical transformation” (345). Hirschfeld described this latter category “as “total” or “extreme” transvestites, for the term “transsexual,” although coined in 1923, was not yet in common use” (345). Andrea Rottmann cites an interesting historical fact – “For postwar East Berlin … authorities continued to issue transvestite passes into at least the second half of the 1950s” (116). Charlotte, aged almost 30 by then, mentions no such pass; she lived on the edge of society within what would always be considered an extreme cohort. Her rejection of the term transsexual is also interesting. Charlotte evidently felt it didn’t describe her situation, but it was also yet another extreme label, and it had associated practical problems too – “Not until 1976 in the GDR and 1981 in the FRG were laws passed allowing individuals to undergo “sex change” surgeries and apply for a change of name and gender status on their birth certificates” (Sutton 349). Without the possibility of hormone treatment or surgery, transsexuality was an unrealisable truth in the sense that a physical transformation was not an option

The more one reads about Charlotte, the more she emerges as an exception within an exception. She could never pass as anything but herself. “Cross-dressers and trans people could hence run into problems if they became conspicuous in public: that is, if they failed to pass” (Rottmann 116). Trouble would ensue if one’s “gender did not read as conventionally masculine or feminine” (116). An account in Charlotte’s book explains that – “It has always been dangerous to go around the streets dressed as a transvestite” (Mahlsdorf 169). Charlotte wore no cosmetics and did not have access to hormone treatment, so her appearance was always readable as male (ref. photos). In contrast, her friend named Christine who cross-dressed in the more stereotypical style, thus passing for a woman, had the misfortune of meeting five Russian soldiers who raped her (Mahlsdorf Ch. 13). The discovery of Christine’s biological sex made no difference in the context of a sexual attack. The world of cross-dressing was a place of very few protections, despite the work of men like Hirschfeld

Charlotte never really disguised anything, and this is a point that is lost in Wright’s play. She said of herself – “‘A strong sense of justice lives deep inside of me, and even more importantly, I feel a kinship with those who live at the edge of society” (Mahlsdorf 34). It is for this reason, along with a love of period furniture, that Charlotte saved the Mulackritze bar and recreated it in the basement of her residence (the Gründerzeitmuseum). In its original location in Berlin, this bar had been frequented by gay men, prostitutes, and cross-dressers. Starting in 1974, Charlotte reopened this space in her house as a meeting point for the queer community of East Berlin. Such stories fade into the background because of Wright’s insistence on placing himself between the character of Charlotte and the audience (as Doug/implied author). This was a misguided decision. The resulting play structure places a perceived moral onus on the author to distance himself from anything unconfirmable or apparently immoral in Charlotte’s story. An audience does not require such an intermediary figure to guide them.

“What may have begun as the playwright’s sincere intention to place before latter-day audiences realistic Holocaust-era re-creation invariably devolves into an impenetrable postmodern melange of tongues and texts – the very melange from which Wright draws Wife’s dramaturgy.”

(Schiavi 207)

Wright won the 2004 Pulitzer Prize in drama for I Am My Own Wife. Despite the issues raised in this essay, the play is exceptionally well crafted and enjoyable as a reading text. For anyone studying trans issues, Charlotte’s story is a testimony to the profound complexity of lived experience as a non-binary person. The fundamental flaw of Wright’s play is the creation of doubt because verisimilitude is essential to such a story. Furthermore, the play positions someone already on the edge of society as even more remote, whereas the core aim should have been the exact opposite.

Works Cited

Abrams, M. H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. 7th Edition, Heinle & Heinle, 1999.

Hansen, Per Krogh. “Autofiction and Authorial Unreliable Narration.” Emerging Vectors of Narratology, edited by Per Krogh Hansen, John Pier, Philippe Roussin and Wolf Schmid, De Gruyter, 2017, pp. 47-60.

Hirschfeld, Magnus. The Transvestites. Translated by Michael Lombardi-Nash, Urania Manuscripts, 1992.

Olson, Greta. “Reconsidering Unreliability: Fallible and Untrustworthy Narrators.” Narrative, vol. 11, no. 1, 2003, pp. 93–109. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20107302.

Richardson, Brian. “Point of View in Drama: Diegetic Monologue, Unreliable Narrators, and the Author’s Voice on Stage.” Comparative Drama, vol. 22, no. 3, 1988, pp. 193–214. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41153358.

ROTTMANN, ANDREA. “Passing Through, Trespassing, Passing in Public Spaces.” Queer Lives across the Wall: Desire and Danger in Divided Berlin, 1945–1970, University of Toronto Press, 2023, pp. 104–33. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/jj.2960283.9.

Saviana Stanescu. “Doug Wright: ‘We Love to See Power Subverted.’” TDR (1988-), vol. 50, no. 3, 2006, pp. 100–07. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4492698.

Schiavi, Michael R. “The Tease of Truth: Seduction, Verisimilitude (?), And Spectatorship in ‘I Am My Own Wife.’” Theatre Journal, vol. 58, no. 2, 2006, pp. 195–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25069820.

Stromberg, David. “Beyond Unreliability: Resisting Naturalization of Normative Horizons.” Emerging Vectors of Narratology, edited by Per Krogh Hansen, John Pier, Philippe Roussin and Wolf Schmid, De Gruyter, 2017, pp. 61-76.

Sutton, Katie. “‘We Too Deserve a Place in the Sun’: The Politics of Transvestite Identity in Weimar Germany.” German Studies Review, vol. 35, no. 2, 2012, pp. 335–54. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23269669.

Wright, Doug. I Am My Own Wife: Studies For A Play About The Life Of Charlotte von Mahlsdorf. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004.