Court, Joseph-Désiré. Death of Hippolytus. 1825, Musée Fabre, Montpellier.

- Play Title: Phaedra: Pity the Monster (monologue)

- Authors: Timberlake Wertenbaker

- Written: 2020

- Page count: 8

Summary

Timberlake Wertenbaker’s Phaedra: Pity the Monster is an adaptation of Ovid’s Heroides 4: Phaedra to Hippolytus. It is one of 15 monologues by a selection of female writers who contributed to a book entitled 15 Heroines: 15 Monologues Adapted from Ovid.

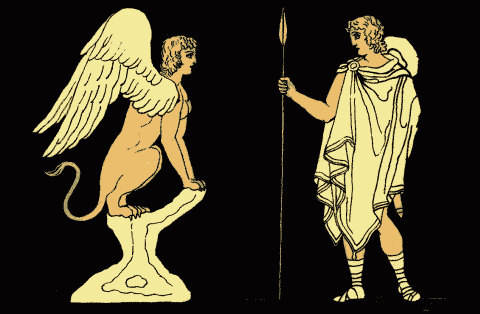

Phaedra is a middle-aged woman with two fully grown sons. She is also stepmother to a stern, young man named Hippolytus. Theseus, Phaedra’s husband, does not favour the oldest of his three sons. In contrast, Phaedra becomes infatuated with the young man. Unable to control her desires any longer and possibly under the influence of a curse, Phaedra pens a salacious letter that is delivered to Hippolytus by a servant. We are not privy to Hippolytus’ reaction, but Ovid writes elsewhere of the young man’s utter disgust upon reading the note’s proposal. Wertenbaker adds nuance to an old story but retains features such as Phaedra’s formidable powers of seduction. Not even accusations of indecorous behaviour or incest will perturb Theseus’s wife. The sordid letter ultimately leads to an accusation of rape, a brutal slaying, and a suicide. Ovid’s tale is reworked to suit a modern audience. However, it captivates as surely as it did when first told to a Roman audience sometime around 26 BC. When reading the monologue, one needs to keep in mind that Phaedra is a half-sister to the much-feared Minotaur of Greek myth.

Ways to access the text: reading

I accessed the text via Everand, which is an online eBook provider. They offer a free trial, so that is an option for non-members. You may also purchase the text via the Nick Hern Books website.

If you are interested in the story itself rather than the particular modern version noted here, then you may search online for Ovid’s Heroides (Heroines). Although the book is easy to find, translations from the original Latin vary in quality so search around.

Why read Phaedra: Pity the Monster?

The original themes and connotations of Ovid’s text have been reworked by a modern writer and the result is several distinct layers of meaning. The interpretative options are quite broad since Phaedra can be seen as an empowered, older woman; a Weinstein-esque sexual predator; or a delusional, sad figure. At its core, the story is still about an amorous, older woman who wants to sleep with her stepson. With the modern adaption comes additional layering. Now, the love letter doubles as a commentary on racism, migration, white privilege, womanhood, and ageing. In other words, the monster becomes all the things that modern society wishes to disown or build barriers against. At this symbolic level, the story comments on contemporary European politics. Greek mythology is momentarily forgotten and one begins to think of Brexit and the recent Rwanda Bill (2024) that sends unwanted, mostly dark-skinned foreigners away. Wertenbaker’s adaptation is subtle but also generous in its interpretative possibilities.

Post-reading discussion/interpretation

Do You See a Monster too?

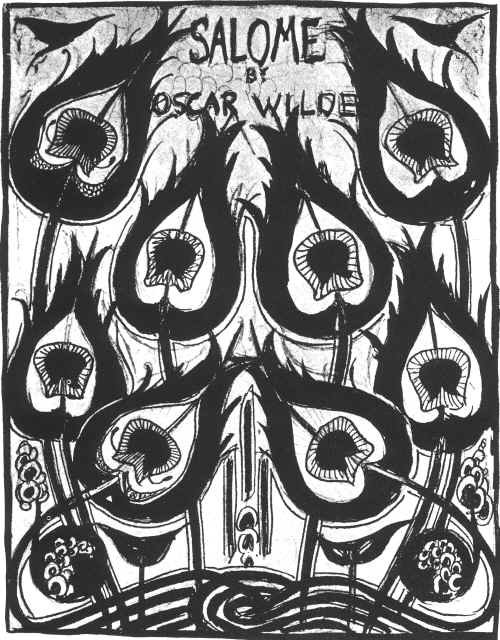

Though far from the first to do so, Timberlake Wertenbaker has tackled the Greek myth of Phaedra. Indeed, not even Ovid’s version was the first. Sophocles and Euripides, both of whom were Greek tragedians from the 5th century BC, wrote about Phaedra and her scandalous desires. Then there was Ovid’s version, which borrowed liberally from his predecessors. In the first century AD, the Roman dramatist Seneca wrote about Phaedra yet again, but afterwards, there was a prolonged literary silence around this mysterious, incestuous figure. The next work deemed noteworthy in literary circles was Racine’s 1677 play, simply entitled Phèdre. In the 20th century, writers as diverse as Eugene O’Neill and Sarah Kane have taken inspiration from Phaedra’s tale to produce new works. Many of the early adapters retained the story’s key points and focused more on diverse ways to craft the characterisation of Phaedra; for instance, the central figure can be an honourable woman brought low by an unquenchable passion or an incorrigible, shameless wench intent on satisfying her loins. Later adaptations have shown how flexible the story can be in the right hands. Phaedra’s tale has never been set in stone and diverse writers continue to bring surprising nuances to how one may view her.

Ovid’s original text Heroides (Heroines) consists of 21 letters in total. The first 15 are mostly letters from mythological women to the men they love. Think of figures from Greek mythology such as Medea and Penelope. The impetus for each letter is a geographical or figurative distance between the female lover and the male love object. In contrast, letters 16 to 21 consist of epistolary exchanges initiated by men and the subsequent replies from the mythological women to whom they wrote. The modern text, 15 Heroines, is concerned with only the women’s perspectives, thus the first 15 letters. Though traditionally described as letters, not even Ovid’s monologues actually conform to this description. To call them letters is merely to allocate a familiar frame by which they can be recognised.

One stubborn obstacle to these spellbinding monologues is the necessity of knowing something about Greek mythology. While Wertenbaker’s text has fewer erudite references than Ovid’s original, the monologue still relies on a reader’s knowledge of a few key facts, otherwise, the story falls quite flat.

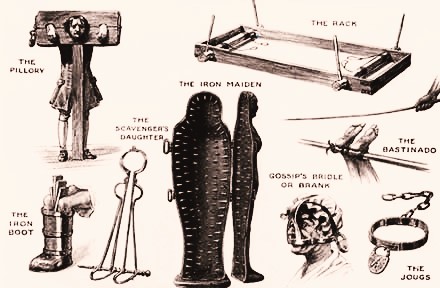

Phaedra’s family tree is a storehouse of Greek myths. Her father was Minos, King of Crete, whose conception was slyly achieved when Jupiter disguised himself as a bull to trick the young princess Europa. She first hesitatingly petted the impressive animal and then foolishly sat on his back, only to be whisked away. She was later defiled by the god and subsequently became pregnant. While Minos was the progeny of a god who simply disguised himself as a bull, Phaedra’s mother, Pasiphae, did the unthinkable. King Minos was away for an extended time waging war against King Nisus, and Pasiphae was all alone. Unbeknownst to the queen, a curse was put upon her by Poseidon on account of her husband’s disobedience relating to a sacrificial bull. The curse meant that she fell in love with this white bull. To satisfy her newfound, taboo carnal desires, Pasiphae asked Daedalus, the gifted craftsman, to make her a wooden cow. By crawling inside this life-like contraption, she could successfully mate with the beast. As a result, Pasiphae gave birth to an abomination that was half man and half bull: the Minotaur.

When King Minos returned home and saw the child his wife had borne, he was determined to hide this shameful thing. Once again, Daedalus’ ingenious craftsmanship was needed so that a mind-boggling labyrinth could be constructed to imprison the beast eternally. Every 9 years, young Athenians (the enemies of Minos) were sacrificed to the Minotaur. When the third feeding was due, a young Athenian warrior named Theseus volunteered to join the other youths who had been allotted this terrible fate. When Ariadne (Phaedra’s sister) saw the handsome warrior named Theseus, she fell in love instantly. In the hope of winning him over, she gave him the famed ball of thread that would allow him to find his way out of the maze. Theseus duly slayed the Minotaur and eloped with Ariadne to the island of Dia, but he soon heartlessly abandoned the girl. Theseus went on to conquer an Amazon woman named Hippolyta, who bore a child named Hippolytus. Phaedra was Theseus’ second wife, with whom he had two more sons. This is a brief overview of the complex links between Phaedra, her sister Ariadne, their half-brother called the Minotaur, Theseus, and Hippolytus (Phaedra’s stepson).

Wertenbaker’s approach to Phaedra focuses primarily on monsters and their monstrous acts. The monologue is a contemplation of anthropomorphism, which attempts to put the non-human in a far more sympathetic light, juxtaposed with the idea of the bestial human, namely the cold-hearted, moralistic Hippolytus. Phaedra proceeds to highlight her family’s genealogy; she is daughter and granddaughter to women famed for being seduced by horned beasts. These women became infamous for their diabolical trysts. Phaedra’s speech clearly references Greek mythology, but there is a more modern topic too concerning an intermingling of peoples, races, classes, and ages. Phaedra understands that she is a monster in Hippolytus’s eyes; it is not just about her family heritage and beastly half-brother, plus the fact that Crete is within view of the dark continent of Africa, but also due to her revelation of sexual longings – her “monstrous thoughts” (Wertenbaker 155). She is a seductress at her core, and her rhetoric is not being expended merely to attain a love poem or song. She desires to know her husband’s son carnally. Employing a decidedly ironic tone, she attempts to repackage her appeal by transforming the idea of the toxic monster. Hippolytus may be convinced that a taste of “the forbidden” (156) will unveil new worlds for him. Phaedra has sufficient hubris to believe that she can convince Hippolytus to act against his own nature. As a huntsman, he sees the animal kingdom as a realm for blood sport, nothing more. Yet Phaedra appeals to him to discover pity and make love to her: someone he sees as a lesser thing, almost an animal.

Phaedra’s plea to Hippolytus, as crafted by Wertenbaker, holds much of the same irony, contradiction, and guile of Ovid’s original. However, one must acknowledge that only half the story is being told. Who is this young man to whom Phaedra makes her plea, and what is his likely response? In Greek mythology, Phaedra and Hippolytus have equally tragic destinies, so one needs to understand that the ageing seductress is always doomed to utter failure. Otherwise, one could far too easily credit her with amazing chutzpah! Alternatively, one could propose that Phaedra be seen through the lens of a sexually liberated, 21st-century audience and, therefore, Hippolytus is not the point. The point is the thrill of the hunt that Phaedra engages in. This little twist of the hunted magically morphing into the hunter is like looking at a Gestalt image and seeing one figure, then the other. The editors of 15 Heroines may have neglected to provide an explanatory introduction for this exact reason, namely, to liberate the tale from Ovid’s old clutches. Alternatively, the book may anticipate an ideal reader and a common reader with the former knowing Greek mythology and the latter being ignorant of it. This becomes problematic since it hints at elitism, yet interesting too because varying interpretations will be the logical outcome. In any case, it is difficult to assert that Phaedra’s love plea has no teleological intent.

Since this essay addresses Phaedra’s entire story, Hippolytus’ part thereof is deemed essential. To excise him from the story would rob us of a better understanding of Phaedra. Paul Murgatroyd et al explain that “In Euripides’ Hippolytus the young prince is intolerant and rather fanatical, a virginal misogynist who will have nothing to do with love or sex” (48). It is quite a description. Indeed, the young man depicted in Euripides’s text is venomous towards women, especially after learning of his stepmother’s feelings. Hippolytus sees women as vain, treacherous, and often promiscuous (49). Of some interest to readers of the modern version is Hippolytus’s view that “women should be housed with wild animals that bite but lack speech, so they can’t talk to other people or get a reply back from them” (49). Women are not just the weaker sex but the hated sex, no better than animals and deserving the company of animals. Therefore, when Wertenbaker’s Phaedra asks Hippolytus to “Pity the monsters” (157), one can fully appreciate how delusional and pathetic this plea sounds. The sheer impossibility of the amorous mission is an intrinsic part of the tale – “There is nothing that Phaedra could have said that would seduce such a character [Hippolytus]” (Murgatroyd, et al 49).

In a performance setting, the Phaedra of 15 Heroines also speaks directly to us, the audience. This character becomes a conduit for an artist like Wertenbaker to express something that sparks recognition. One example is the way Hippolytus is accused of being the default of perfect normality: a youthful, toned, (white) male (body). Older women are deemed invisible and thereby become de-sexualized, dehumanized, spaces of utter absence, whereas Hippolytus has automatic membership in an exclusive, powerful club. Agedness, femininity, and being foreign are all signs of imperfection. The monologue lends itself to being read as a political allegory. Shutting out the other is judged to be a faulty mindset.

“Hear the monster, pity the monster and then even love the monster.

We roam that other world. You have borders against us, barriers, definitions. You lock us out, you think you’re safe.

But who is locked in?” (Wertenbaker 155)

The playwright is a UK resident, so it is quite easy to read the above text as a Brexit reference. Immigration and border concerns were a key factor in deciding the 2016 referendum. Foreigners arriving on boats from Africa were/are not being welcomed in any European land. When Phaedra confronts Hippolytus, positioning herself as the other, she says “stop demanding praise from us. Stop assuming we deserve our humiliation” (156). The apparent analogy between monster and migrant facilitates a different version of the predator and prey scenario that Phaedra speaks about so extensively. Foreigners become fodder in the voracious economies of countries like England because they feed the capitalist system with cheap labour. Migrants are often employed in jobs deemed too menial or too low-paid for UK-born nationals. The contradiction soon arises that the workers so desperately needed become utterly despised since they are automatically placed at the bottom of the social hierarchy. Just like Phaedra, should migrants be grateful and accept their lot, even if it is humiliating? Phaedra’s monologue is a lover’s plea that echoes to us from ancient times, yet also a potent political comment on the current migration situation, which has become so contentious in recent years.

Depending on one’s impression of Phaedra’s confessional letter to Hippolytus, various endings can be imagined. In Greek myth, however, the story has been committed to paper long ago, and the conclusion is tragic. Admittedly, various versions arrange the details differently, but the key events are always the same. First, Phaedra’s secret love for her stepson is put in a letter; revealed to the young man by a wayward servant; or Phaedra herself tells Hippolytus. His reaction is always the same: sheer disgust. In utter humiliation, Phaedra takes her own life (either before or after Hippolytus has died). The unexpected twist in the story is that Phaedra’s shame prompts her to accuse Hippolytus of rape. This is an attempt to save her good name posthumously and thereby protect her sons’ reputations too. Theseus believes the false charge and banishes his eldest son, but the king additionally calls on Neptune, god of the sea, to punish the rapist. The cause of Hippolytus’ death is strangely poetic, at least from a literary point of view, since the theme of the monster looms large. Ovid recounts the story in The Metamorphoses as follows:

“the sea rose up, and a huge mass of waters seemed to curl itself into a mountainous shape from which, as its size increased, came bellowing roars. Then the summit seemed to split, and there erupted a horned bull, which burst through the waters, rearing itself into the yielding air, till its chest was clear of the waves, vomiting quantities of sea water from its nostrils and gaping mouth.”

(Ovid 348)

The horses of Hippolytus’ chariot take fright and they all crash. Hippolytus becomes entangled in the reins while the rest of him is pulled violently in the opposite direction. Despite the many beautiful images of this scene in classical art, Hippolytus’ injured body is described as “one gaping wound” (Ovid 348). It is fitting that Neptune assumed the shape of a monstrous bull, reminding one yet again of Phaedra’s half-brother.

The modern version of Phaedra’s monologue ultimately achieves a lot. It is a text with strong political undertones that cleverly underpin the story of an older woman’s seductive plea for openness to new experiences. Phaedra’s call for pity, not empathy, is intriguing and is an addition to the story made by Wertenbaker. Since Phaedra wants to bed the young man, this call for pity is simply a clever ploy that will appeal to his sense of superiority. Less flatteringly, Phaedra is simultaneously revealed as a woman who would welcome being made love to, even if it makes the young man feel debased. This particular situation has earned quite a crude modern label. The monologue’s labyrinthine complexities become clearer when one compares it to Ovid’s original where Phaedra makes some outrageous claims to get Hippolytus into bed. For instance, there is a suggestion that he will take her virginity – “You’ll reap the first-fruits of my unsullied reputation” (Murgatroyd, et al 44). She says this despite the fact that she is a mother to two sons and the wife of a notoriously oversexed king. On the other hand, one cannot help but be mesmerized by her sustained plea.

“Here is the forbidden: the wife of your father. Not young, indeed to you old, not perfectly formed, spilling out, in shape and feelings, a woman, the unknown, uncontrolled.” (Wertenbaker 156)

The purpose of the monologue is to test our resistance to Phaedra’s powerful language. She is a magically duplicitous character whose deep heritage clings to modern retellings of her tale. Wertenbaker is also acutely aware of her character’s literary history since she translated Racine’s Phèdre from French into English (2009). In the end, does one see the monster that Hippolytus sees, or a vibrant, dangerous, older woman? In truth, it is impossible to vilify Phaedra or sympathise with her entirely. Wertenbaker has successfully updated an ancient text and retained the essential complexities as well. There is an enchanting charisma to a lie that, nonetheless, contains much truth. The manner in which Wertenbaker has linked these truths to modern politics is a bravo moment.

Works Cited

Murgatroyd, Paul, et al. Ovid’s Heroides: A New Translation and Critical Essays. Routledge, 2017.

Ovid. Metamorphoses. Translated by Mary M. Innes, Penguin Books, 1973

Wertenbaker, Timberlake. “Phaedra: Pity the Monster.” 15 Heroines: 15 Monologues Adapted from Ovid. Nick Hern Books, 2020.