- Play title: Machinal

- Author: Sophie Treadwell

- Published: 1928

- Page count: 83

Summary

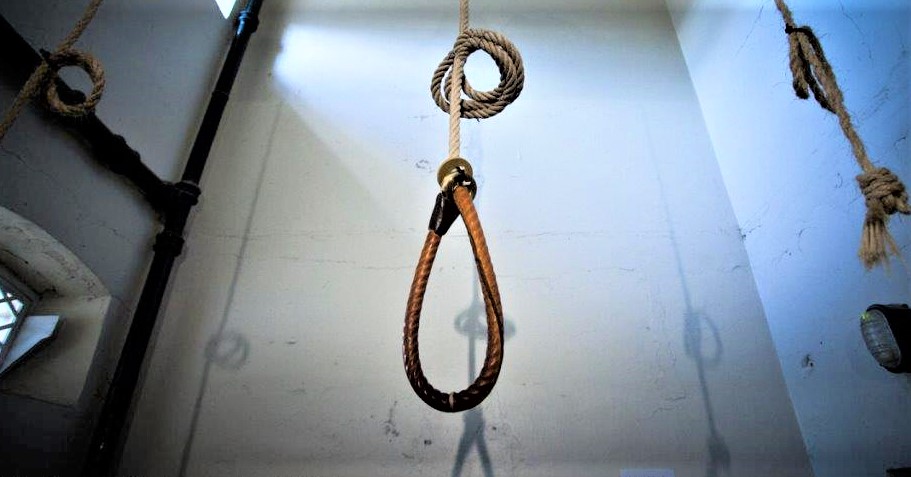

Machinal is a play by American writer Sophie Treadwell. It is largely based on the trial and execution of murderess Ruth Snyder who was the first woman to be sentenced to death by electrocution in New York State. Treadwell’s work is not divided into acts like traditional plays but is told instead in nine episodes. Each episode shows how the central character of Helen Jones, simply referred to as Young Woman, struggles with the progressively challenging and ever-changing roles that society imposes upon her. Treadwell’s own words from the play’s introduction offer the best summation of the story: “The plot is the story of a woman who murders her husband – an ordinary young woman, any woman.” The protagonist, Helen, is a sensitive, anxious woman who grapples with life until she finally commits a horrible crime. A defining feature of the work is Treadwell’s use of expressionist techniques. For instance, there are onstage and offstage sounds of various machines ranging from office equipment to riveting tools on a construction site. Treadwell explained the title Machinal as “machine like,” and it may also be rendered as mechanical or automatic.

Ways to access the text: reading

The text of this play is not difficult to source for free online. For example, the webpage ciaranhinds.eu/pdf/machinal.pdf has a scanned copy of the play.

Advice to readers – the first episode of the play is 12 pages long and not particularly reader-friendly due to short exchanges of highly repetitive dialogue, but this occurs only in the first episode. A persevering reader will later appreciate why the playwright uses this artistic effect to begin the work. The rest of the play is indeed reader friendly.

To my knowledge, there is no audiobook version of the text.

Why read Machinal?

Reasons to Murder One’s husband

It is not a spoiler to reveal that the play’s female protagonist murders her husband. Even if a reader skips the play’s introductory notes, it can easily be guessed from the parallel with Ruth Snyder’s story. The pressing question is why the character of Helen Jones murders her husband. Treadwell presents Mr George H. Jones as a successful businessman who provides his wife with a lovely home and even financially supports her elderly mother. Mr Jones is not depicted as having any of the stereotypical flaws that would account for a wife’s revenge; he is not a drunk, a wife-beater, or an adulterer. The one thing that truly disgusts Helen Jones is her husband’s “fat hands,” but this is surely no justification for murder! Treadwell’s depiction of Mr Jones is captivating as he is, in many respects, a nobody. Yet his murder is the pivotal point of Helen’s life. If the playwright depicts a responsible, benign husband, then surely the motive for murder rests elsewhere. The presence of a motive that is not linked to the victim, but may be found elsewhere, is the abiding message of this play. Will a reader discover that Helen is a monstrously selfish and cold-blooded killer like the media depiction of Ruth Snyder, or perhaps there is some broader societal problem that drives Helen to her crime?

9 Defining Episodes

Treadwell presents an audience with nine individual, self-contained scenes to communicate the play’s full story. In the playwright’s own words, “The plan is to tell this story by showing the different phases of life that the woman comes in contact with, and in none of which she finds any place, any peace.” The phases of Helen’s life that Treadwell is referring to include both the normal and the unusual. Helen is a single working woman, daughter, wife, mother, adulteress, lover, obedient wife, defendant, and condemned woman. The striking element of Treadwell’s words is that Helen never has a sense of place or peace. She is always somehow alienated or at least feels alienated from the first four phases/roles that most women would experience in life (listed above). One may also focus on Treadwell’s decision to use “episode” to name the scenes. For instance, a woman ‘having an episode’ has the connotation of someone acting out or misbehaving: often because of feeling overwhelmed. Indeed, in all nine episodes of the play, Helen never conforms to societal expectations and often displays high levels of anxiety. Therefore, one may interpret each episode as an encapsulation of specific challenges in that life-stage role, for example, the role of a daughter in “At Home.” In this way, one comes to understand why Helen reaches the emotional crisis that she does at the play’s conclusion.

Post-reading discussion/interpretation

Expressionism.

Machinal is a much-lauded example of expressionist drama. M. H. Abrams describes how “The expressionistic artist or writer undertakes to express a personal vision – of human life and human society. This is done by exaggerating and distorting what, according to the norms of artistic realism, are objective features of the world, and by embodying violent extremes of mood and feeling.” As an impressionistic style is therefore quite distinctive, it is worth analysing how it may contribute to a reader’s better understanding of a playwright’s chosen topics. It is noteworthy that expressionism does not have prescriptive rules, and this is also evident in Treadwell’s play. She addresses the true-life story of Ruth Snyder, which suggests a realistic approach that expressionistic artists generally rejected. However, there are other topics that Treadwell addresses in an attention-grabbing, expressionistic style, namely, an ever more modernized, technological society and the role of women within that society. One may view the Snyder story as a necessary anchor to the real world in a predominantly expressionistic play. Indeed, Treadwell prepares the reader for a decidedly subjective depiction of the world in the introduction when she describes her main character as “essentially soft, tender and the life around her is essentially hard, mechanized.” As a result, one witnesses a protagonist who experiences great difficulty manoeuvring the normal phases of life because she views these phases as “mechanical, nerve nagging.” This essay will explore Treadwell’s impactful, impressionistic style and how it serves to communicate the life experiences of Helen. To determine which aspects of the play deserve special focus, one may follow a guiding quote by Abrams: “Expressionist dramatists tended to represent anonymous human types instead of individualized characters, to replace plot by episodic renderings of intense and rapidly oscillating states, [and] often to fragment the dialogue into exclamatory and seemingly incoherent sentences or phrases.” As such, characterization, emotional states, and dialogue are key factors for understanding an expressionistic drama.

The play opens with “Episode One – To Business” and this is arguably the most impactful scene due to its impressionistic style. Regarding characterization, Treadwell gives the office staff no names, so they are identified only by their tasks such as “adding clerk” and “stenographer.” This technique renders the scene universal: it becomes the typical office environment. Yet the playwright chooses to distinguish two characters; the boss retains his proper name of Jones, and Helen is alternately called “young woman” and “Miss. A.” In this way, Treadwell immediately establishes a hierarchy of importance. There are mere staff who remain anonymous workers, then a woman identified by her youth and sex, and finally the boss Jones at the apex of power.

When one begins to consider the emotional states of the characters, then Helen becomes the obvious focus. Helen’s thoughts are vividly expressed at the end of the first scene via a stream-of-consciousness technique that employs a distinctive telegraphic style: individual words, part sentences, and names – all separated by dashes. This initial scene’s closing monologue of thoughts expresses Helen’s intense doubts about marriage. She craves freedom from the office and her mother too; however, thoughts of marriage trigger her feelings of disgust towards Jones. Her words “something – somebody” will be repeated throughout the play at crucial moments to express her desperate search.

The third distinctive feature of expressionistic drama is the style of dialogue. In the first scene, the dialogue is staccato and highly repetitive. The key repetitions range from the obsequious “good morning,” which is said to Mr Jones, to the accusatory “you’re late” said to Helen, which is followed by the staff’s chanted, expectant cries for her to provide an “excuse.” As Helen is Mr Jones’s object of desire, she has inadvertently raised her head above the parapet and is now open to criticism. When one inspects the content of the dialogue, it is a tangled mix of mundane office talk and gossip about Miss. A. (Helen) possibly marrying Jones. For example, the filing clerk asks, “What’s the matter with Q?”, which refers to a filing task but covertly refers to Jones’s possible marriage proposal to Helen. The staff responses highlight the secret meaning of the problem of Q: “Has it personality? … has it halitosis? … has it got it?” Similarly, the adding clerk guesses Jones’s income aloud, and the stenographer types a business letter while considering the possible marriage: “Will she have him? This agreement entered into – party of the first part.” The jumbled dialogue alerts a reader to the only topic of interest in the office – will the boss marry Helen? The dialogue also alerts a reader to how business and romance are being melded together unnaturally. In the first scene, Treadwell already manages to distance Helen from the others and shows her story’s importance.

The special value of the impressionistic technique used by Treadwell links to the oppressive, sombre tone of the scene. By anonymizing the office staff, the playwright depicts practically every office environment imaginable. The workers are akin to worker bees. For instance, the stenographer is the epitome of a conscientious employee because she is punctual and productive; however, she is described as a “faded, efficient woman office worker. Drying, dried.” The description denotes a wasted life. The office sounds, as per the stage directions, are bells, buzzers, and typewriters – all metallic, mechanical sounds that fall harshly upon the human ear. Thus, the environment is unnatural and even soul-destroying. The only topic of conversation, apart from office duties, is Helen. She is the sole person who may eventually escape office life – and forever have “breakfast in bed” if she marries Jones. The repetitive nature of the conversation, like the background machine noises, gives the impression of a grey, unimaginative office environment in every respect. However, Helen is somehow different. The adding clerk says, “She doesn’t belong in an office” and that “she’s artistic.” Treadwell grants Helen a semi-identity as “Miss. A.”/“young woman,” but such titles also highlight a dilemma. Helen is only special because of Jones’s romantic interest in her. Treadwell counters this classification. She draws attention to Helen’s emerging personal identity while also expertly capturing the emotional state of the young woman. The playwright achieves this by showing Helen take two important actions: first, Helen steps out of the crowded subway carriage, and then later in the office, she flinches when Mr Jones touches her shoulder. As such, she symbolically steps out of the unthinking melee of modern society and pardons herself from the rat race. This refers not only to the nameless thousands in subway carriages on their way to work daily, but also, all the “young, cheap and amorous” women like the “telephone girl” who would readily marry a boss like Jones to get ahead in the world. Helen stands apart from the masses. Helen’s closing thoughts succinctly convey her anxiety about wanting to gain freedom from the drudge of office life; yet she has only one escape route, namely marriage to George H. Jones. Her angst-ridden message delivered in the efficient, telegraphic-style text reflects how her life is inescapably shaped by the technology of the era and the men in charge. In some respects, Helen’s escape seems quite illusory. Treadwell’s strategy is to win over the reader as an ally of Helen’s by artistically presenting the world that the young woman inhabits. The chief characteristic of the tone of the first scene is that it communicates how the world feels to Helen. Even though she tries to be herself and unique, she is trapped. The first crucial episode of Helen’s story presents her in a sympathetic light and wins over an audience.

In all, Machinal addresses three distinct yet frequently overlapping topics: a real-life murder case, the modern world, and feminism. The verisimilitude of the drama is most evident in the fact that Ruth Snyder was indeed tried and convicted of murder in New York in 1927. For this reason, it is unnecessary to outline in detail the overall facts of Snyder’s case. The only exception will be major alterations to the story made by Treadwell. The two other key aspects of the story, namely the modern world and feminism, are dependent on the techniques of expressionistic art to gain true communicative force in the drama. The opening scene is exemplary of impressionistic techniques, but the play has nine episodes in total, so it is necessary to provide a broader overview.

Treadwell named her drama Machinal, which means “machine like,” and this refers to her view of modern life. One prominent expressionistic feature of the work is that the playwright relies heavily on sound to communicate the oppressive, emotionally draining reality of the modern world. When considering the play’s sounds, one must first differentiate those that are consoling to Helen from the other stressful, cacophonous sounds. For example, Helen welcomes the sound of the Negro spiritual song when she is in her prison room. She says, “I understand him. He is condemned.” She is also pleased by the sound of “Cielito Lindo” (Little Heaven) played on a hand organ, which she hears with her lover Dick Roe. Helen also remembers hearing the sound of the sea as a child when she held a “pink sea shell” to her ear. Treadwell demonstrates via these pleasant, consoling sounds that Helen can indeed experience true calm. This serves to undermine any impression that Helen is “crazy” as her mother labels her or “neurotic” like her doctor says. In particular scenes, the soundscape is crucial to effectively convey Helen’s intense negative feelings. In “Episode Two – At Home,” Helen tries to ask her mother’s advice on marriage, but the scene is characterized by noisy interruptions of all kinds. A multitude of aural stimuli are concurrently active: the radio, neighbours’ voices, the buzzer, her mother’s nagging/complaining and the clatter of dishes. Helen’s tension is first apparent when the garbage man buzzes, and she jumps up from the table (like every night) prompting her mother to chide – “you act like you’re crazy.” In this scene, Treadwell meticulously intertwines the overheard neighbours’ conversations with Helen’s questions to her mother. The neighbours talking points are various: parental control – teenage lovers’ trysts – a husband who does not account for his nights out – a husband’s kiss that is a prelude to unwanted sex. Thus, Helen’s own story, her past, and her foreshadowed future come in echoes through an open window while her mother sits dumbly opposite her, unable to answer the most basic of questions. The neighbours’ overheard conversations are the acoustic detritus of daily life, yet they contain essential common knowledge. Helen’s frustration builds due to her mother’s silence about these everyday issues. A wall of sound frays her nerves while her questions are met with stony silence.

In “Episode Five – Maternal” the sound of a riveting machine grates on Helen’s nerves. The explanation for the sound is that a new hospital wing is being built. The result will be the “biggest Maternity Hospital in the world” with the obvious connotation of a baby production line. A doctor orders Helen’s nurse to “put the child to breast” while Helen shouts “no,” and the riveting machine sounds in the background. The analogy is that a mother who fails to bond with her child will have it forcibly fixed to her breast just like someone may rivet two pieces of metal together. There is a suggestion that Helen is suffering from postnatal depression, so the analogy of mechanical bonding gives full expression to the doctor’s cruelty. The communicative effectiveness of the scene relies on the odd sound effect. To conclude this brief analysis of Treadwell’s critique of modern, mechanical life by using sounds, one may look to episodes eight and nine: “The Law” and “A Machine.” In the courtroom, Helen’s personal story is slowly being appropriated by journalists and this is communicated by the incessant “clicking of telegraph instruments offstage.” In the final scene, the convicted woman’s speech is cut short on no less than two occasions. Initially, she tries to impart a message to her own daughter, saying “Tell her –,” but she cannot finish as “it’s time” (execution time). Finally, as Helen sits in the electric chair awaiting the moment of death, she tries to speak but cannot finish: “Somebody! Somebod-.” The gradual depletion of Helen’s power of self-expression is first paralleled by the burst of activity from journalists and their telegraphic messages. The electric chair itself is the ultimate machine of the modern world and it shows how Helen may be totally and instantaneously silenced.

One may classify Machinal as a feminist work due to Treadwell’s apparent sympathy for the female protagonist in various life phases/roles: daughter, wife, mother, and finally condemned woman. Treadwell makes clear that women’s choices in 1920s America were highly restricted. Helen’s despairing plea for “something – somebody” at the close of episode one is never answered, as proven by her last word, “somebod-.” While Treadwell uses sound to great effect to communicate an oppressive, dehumanized, technological force, the main tool used to communicate Helen’s predicament is simply language. Impressionistic dialogue is stylistically fragmented and frequently incoherent. Yet it is not the typography that holds the key but how it reflects the failures of communication in any given scene. One needs to look at more than Helen’s fragmented sentences and her telegraphic style of delivery; there is also irremediable miscommunication between the sexes and between different generations too. In short, Helen’s language fails but not in the conventional sense. The first major example is Helen’s crucial discussion with her mother about marriage. Helen’s full question may be broken down into three segments.

“All women get married, don’t they?”

“Oh Ma, tell me! … About all that – love!”

“Your skin oughtn’t to curl – ought it – when he just comes near you”?

These questions are somewhat pitiful as they expose Helen’s lack of experience and her resulting vulnerability. Helen’s mother has already decided that marriage is the best option for Helen. The older woman is prejudiced on account of Jones’ position as company Vice-President, and his agreement to financially support his future bride’s ageing mother. While Helen flails about trying to express her thoughts, in quite an emotional state, her questions are still surprisingly clear, for example: “When he puts a hand on me, my blood turns cold. But your blood oughtn’t to run cold, ought it?” Nonetheless, Helen’s mother treats her daughter’s pleas for advice as if they were truly incoherent, illogical and crazy. The responses that Helen receives display the older woman’s obstinate unwillingness to assist in any way: “Tell you what? … Do you what? … See what? The mother has already concluded that a company Vice-President must be a “decent” man and that love does not “pay the bills.” Treadwell highlights that the women are separated by both a generation gap and their colliding world views. Helen has open-heartedly explained her anxieties, but her mother replies with, “nonsense … you’re crazy.” Helen’s frustration at her mother increases exponentially and leads to an emotional outburst – “Ma – if you tell me that again I’ll kill you! I’ll kill you!” This is a defining moment in the play as Treadwell depicts the explosive anger that may emerge from a sense of powerlessness. Plain, normal language has somehow failed Helen. The kernel of the problem is the apparent contrast between a young woman’s expectations of life versus the practical, decidedly anti-feminist views of an older woman. The scene may also be interpreted as a foreshadowing of Helen’s eventual crime of murder. Treadwell’s message is that Helen who is just “an ordinary young woman” faces immense challenges due primarily to the position of women in society. Helen’s language fails because women have no real power in society. The implicit feminist warning is that Helen is an ‘Everywoman,’ and therefore, any woman could end up in the same position.

The specific failures of language between the sexes are depicted in multiple scenes. “Episode Three – Honeymoon” is an unusual example because Helen says “no” a considerable number of times but never to the question that one anticipates hearing. For instance, when she is undressing in the bathroom and her husband says that he is coming in, she replies, “No! Please! Please don’t.” Mr Jones goes on to declare, “I’m your husband, you know,” and this implies specific marital rights, and therefore, certain requests are deemed redundant within a marriage. As such, Helen’s multiple responses of “no” are in vain since her husband will never ask permission for what he now sees as a right, namely conjugal rights to sexual relations. Helen starts to weep and cries out plaintively for her mother. She realises her powerlessness. Later, when Helen states her daughter’s age in court as being, “she’s five – past five,” then in the context of a six-year marriage it seems the child was conceived on their honeymoon. The honeymoon scene requires a reader to comprehend the failure of language as going beyond the mere spoken word because Helen’s obvious signs of distress and anxiety are also readable.

Treadwell depicts a more overt example of miscommunication in the hospital. When the nurse makes a note on Mrs Jones’s medical chart that the patient was “gagging,” then the doctor interprets it quite literally, “gagging – you mean nausea.” But the nurse’s ensuing attempt to explain is rejected. The gagging was Helen’s anxious response to her husband’s visit – a strong emotional reaction, which is later given full expression in Helen’s thoughts about the breeding dog Vixen. Helen thinks her lot in life is no better than that of a breeding dog since she was impregnated with a child she did not want. At the close of the scene, Helen says, “I’ll not submit any more” and this apparently refers to non-consensual sex. Treadwell puts the onus on her audience to look at each of these scenes with a more intuitive and less literal eye. Take for instance the use of irony in “Episode Seven – Domestic” when Mr. Jones reads aloud a serious newspaper article to his wife, quoting, “All men are born free and entitled to the pursuit of happiness.” The meaning of the quote in the context of the play is excruciatingly literal: men and only men have freedom. In contrast, Helen’s reality is reflected in the tabloid headlines that she silently reads to herself, “girl turns on gas … woman leaves all for love … young wife disappears,” and these are the solutions she envisages. Finally, in the male environment of the courtroom (a male judge and all-male jury), language is also distorted as it begins to conform to legal requirements. One illustration is that a six-year marriage without a quarrel is unquestionable evidence of a “happy marriage.” In all, Treadwell displays how language fails due to the selfish concerns of an obstinate interlocuter (Helen’s mother), due to an obtusely literal interpretation of a patient’s symptoms (Helen’s doctor), due to an old-fashioned and legally defined environment (marriage). In the final scene, Helen’s speech is fragmented and left unfinished because she is executed.

Treadwell achieves remarkable success by taking as her topic the media sensation that was the trial and execution of Ruth Snyder and then presenting the story in an expressionistic drama. The playwright takes advantage of the notoriety of the murder as a hook to catch the public’s attention before bringing them on a new journey as she retells the story. As explored, the specific style of expressionism elevates Treadwell’s work, especially as it relates to characterization, emotional states, and dialogue. The playwright manages to communicate uniquely by placing before the audience a vivid impression of how Helen sees the world.

Sympathy for a Murderess

Treadwell’s play challenges a reader to have sympathy for the character of Helen Jones. The playwright effectively reframes the Snyder story and presents it to an audience who must adjudicate anew on the crime. While one may indeed sympathize with Helen’s plight, the rhetorical force of the presentation asks that one accept, maybe just tentatively, Helen’s motive for murdering her husband and this aspect of the play bears further discussion. The public came to know the real-life murderer Ruth Snyder only through the intense media attention on the court proceedings. Treadwell elaborately depicts Helen through all her most important life phases thus creating a comprehensive background story. The playwright controls the narrative and as Abrams writes, “the expressionist artist or writer undertakes to express a personal vision – usually a troubled or tensely emotional vision – of human life and human society.” As such, the character of Helen serves a communicative purpose and that is to disseminate Treadwell’s particular perspective on the real-life murder case. In the play, Treadwell depicts how the media take over Helen’s story once it becomes public (as happened to Snyder), and therefore, the playwright is regaining control of the narrative in Machinal. This new presentation of the story means each reader must decide if Helen’s punishment is deserved or unfair.

It is a salient point that Helen is depicted as having no power over her own story or her direction in life. In the first scene, we are told that Helen’s “machine’s out of order,” and because she is a stenographer, this means her typewriter. Treadwell, who was a journalist herself, would have understood the immense power of the typewriter for a woman. It is the machine that allows one to author one’s own story. Yet Helen only takes down letters dictated by Jones. Helen’s lack of control over her own narrative is most evident during the court case when her defence lawyer defines her as “a devoted daughter, gentlemen of the jury! As well as a devoted wife and a devoted mother!” Although a strong defence strategy, it precludes Helen from ever admitting to an unhappy marriage. The definition not only misrepresents Helen’s life but crucially removes any burden of fault from her late husband and forces one to seek a motive elsewhere. In this example, Helen’s trajectory is determined by her lawyer, but this has been Helen’s plight all along. She has constantly sought “something – somebody” to save her. Helen is eternally seeking a saviour, which indicates her own perceived or indeed actual powerlessness. In an interesting twist, Treadwell depicts Helen as the dupe in the single scene where she appears to gain her freedom, namely, “Episode Five – Prohibited.” What is enlightening about this scene, besides the fact that Helen meets her future lover Richard Roe, is that each of the four men depicted in this scene manipulates another person. (1) A married man named Harry Smith arranges to have sex with the telephone girl. (2) The “middle-aged fairy” seduces a boy. (3) A man convinces his girlfriend to have an abortion. (4) Roe seduces Helen using the cliched line about her being “an angel.” The remark that the gay man makes – “Poe was a lover of amontillado” – is not just about a favourite drink; it is also an allusion to Edgar Allan Poe’s story “The Cask of Amontillado” where a man entombs his friend in a cellar and leaves him to die. Treadwell’s scene “Prohibited” is a masterclass in the entrapment techniques that men use, and this scene highlights the true motive for murder in the play.

Helen’s motive for murdering her husband is certainly the conundrum of the play, and depending on how one interprets the text, the resulting answer may be different. Deciphering the true motive has an enormous impact on one’s sympathy or lack thereof for Helen. There are two main avenues of possible speculation. Helen’s motive is either her affair with Roe, the motive accepted as true in court, or one may look instead to her marital circumstances. Treadwell favours the latter in a sympathetic depiction of Helen.

If life itself feels mechanical to Helen, then the ominous clicking shut of the mechanism, the ultimate entrapment, may indeed be marriage. Like a business deal, marriage is a legal contract. Helen makes two major mistakes upon entering a marriage with Jones. First, as she tells her mother, “I don’t love him,” and second, she does not know if her disgust toward him will fade away, “You don’t get over that, do you – ever, do you, or do you?” The subsequent challenges of Helen’s marriage are not stated outright. However, marital rape is strongly inferred by her “helpless, animal terror” on her honeymoon night and by the fact that she later bears Jones’s child. Any mention of marital rape is problematic as it is anachronistic in the context of 1920s America: a crime that did not yet exist in law and possibly not in social consciousness either. Trauma is suggested in the hospital scene by Helen’s rejection of her newborn child and the fact that her “milk hasn’t come yet,” which is sometimes a result of stress hormones. Helen is eventually shown to capitulate to her role of obedient wife in episode seven, “Domestic” when she provides “rote” responses to her husband’s questions. The problem of dissolving her marriage (divorcing her husband) is a combined problem of financial dependence and a lack of options. Helen married Jones to escape the oppressive office routine, and with the marriage came not only her own financial security but also a monthly allowance for her mother. In 1920s America, a marriage could only be ended with a divorce after one party had been proven to be at fault. The accepted grounds for divorce were abandonment, mental illness, cruelty, or adultery. Therefore, Helen would not only have to admit personal fault to escape her marriage. This would result in an immediate loss of her financial security and her mother’s too. Even though, as stated in court, divorce was indeed the obvious solution to a bad marriage and not murder, Helen’s hyper-sensitivity and associated difficulties made her unsuited to the workplace and highly dependent. Helen decides at some point not to pursue a divorce but to plan a murder instead.

The idea for the murder weapon comes from Richard Roe and the background story is significant. He describes how he was once taken hostage by “a bunch of bandidos,” and he goes on to justify their murders by stating, “I had to get free, didn’t I?” The simple comparison is that Helen feels utterly trapped in her marriage. The situation is complicated further by her mother’s dependence on Jones’s monthly payments. When Roe speaks of freedom in Mexico, Helen replies, “I’ll never get out of here.” Despite all these stated motivations, it is difficult to excuse Helen’s desperate resort to murder.

In court, Helen’s affair is accepted as her motive for murdering her husband. The prosecution lawyer introduces Richard Roe’s signed affidavit, which he says supplies “a motive for this murder – this brutal and cold-blooded murder of a sleeping man.” Roe’s affidavit forces Helen to confess to the crime, so the document seals her fate. To digress a moment, Treadwell has changed the original story in a quite conspicuous way here because both Ruth Snyder and her lover Judd Gray were tried, sentenced, and executed in real life. In the play, Roe not only lives free in Mexico, but he betrays Helen by providing the only evidence capable of convicting her. Thus, the hint of betrayal intimated in the bar scene (“Prohibited”) actually happens, but it serves the purpose of arousing our sympathy for Helen. Her ideal man, the ‘somebody’ she had waited for, turns out to be a cad. Furthermore, the general unreliability of Roe displays that the affair as a motive for murder is flawed for three separate reasons. First, Helen visited Roe’s apartment almost daily while still married to Jones but remained undetected and therefore unrestricted in her actions. Secondly, Roe was a self-confessed womanizer who rejected Helen’s talk of a shared future on their first meeting by replying “quien sabe” (who knows), so he was evidently not marriage material. Finally, while the timeline of events is somewhat vague, Roe clearly ended the relationship at some earlier point as he had subsequently moved to Mexico. While the affair proves Helen’s adultery, it is not automatically a motive for murder since Roe offered her no future prospects. To accept the affair as a motive for murder is only credible if one believes that Helen is exceptionally naïve. .

The actual, or at least most probable, motive for Helen murdering her husband is the trauma of forced submission. This is not limited to what Helen endures in her marriage but may be understood to also include the context of women’s limited rights in that historical era. In expressionistic drama, a distorted representation of the world is used to communicate the character’s emotional state. Nevertheless, the emotional state is true, lived, and has consequences. Helen’s repeated plea for “something – somebody” is a plea for help, a plea for salvation, which is never satisfied. Instead of receiving help, the protagonist is met with increasingly humiliating demands to submit. Helen must submit to her mother’s selfish advice, to her boss’s “fat hands [that] are never weary,” to non-consensual marital sex, to bearing a child, to public betrayal by her lover Roe, and finally to the prison barbers who shave her hair. Helen cries out, “Submit! Submit! Is nothing mine?” Treadwell depicts how a woman who loses all hope of escaping a dire situation may indeed become a killer. Helen explains to the priest the feeling associated with murdering her husband – “when I did what I did I was free! Free and not afraid!” Helen importantly distinguishes between the murder and “that other sin – that sin of love.” Killing Mr Jones makes Helen free; it is a crime she does not repent. A life with Richard Roe is never a true prospect for Helen, but he proves that she is capable of love and that love is indeed possible in life. In the real case, Ruth Snyder, upon hearing that the trial jury would be all men, said the following.

“I’m sorry. I believe that women would understand this case better than men, and then women have a better sense of justice.”

Treadwell echoes this sentiment because she places the reader, as best she can, in Helen’s shoes. It is not the cold logic of the situation that determines how Helen acts in this pitiful saga but instead what she instinctively feels are her options. It is not possible to be sympathetic to a murderess whose only excuse for her crime is an unhappy marriage. Many women would have endured much worse situations than Helen. Similarly, it is not possible to be sympathetic to a woman who kills her husband because she seeks freedom to have an extramarital affair. Yet it is possible to empathize and indeed sympathize with a woman who cannot deal with a situation anymore, who feels utterly trapped and chooses the wrong escape plan. Treadwell’s retelling of the Snyder story presents an ‘Everywoman’ who becomes a killer. Under the wrong circumstances, the housewife who washes the dishes with gloved hands may become the (almost) perfect gloved killer who leaves no fingerprints. Helen’s refrain of “something – somebody” used in court to describe the fictional killers proves that when there was no outsider to help, she resorted to saving herself. It is a cautionary tale about the risks of endlessly making someone submit, leaving them powerless, especially if that someone can be seen as a representative of the entire female sex.

Works Cited

Abrams, M. H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. 7th ed., Earl McPeek, 1999.

“Gray to Seek Trial Outside of Queens.” New York Times, 26 March 1927.

Treadwell, Sophie. Machinal. Nick Hern Books, 2003.