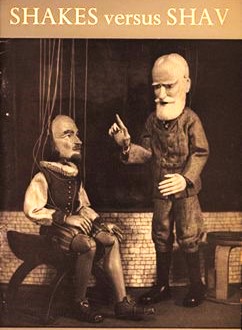

Cover image from Shaw’s puppet play from 1949.

- Play Title: Dark Lady of the Sonnets

- Author: George Bernard Shaw

- Published: 1910

- Page count: 42 (introduction & play)

Summary

This play is a short comedy about a fictional, knockabout encounter involving Shakespeare, the ‘Dark Lady,’ and Queen Elizabeth I. George Bernard Shaw wrote this piece as part of his endeavour to raise funds for the building of a national theatre in England. The play has four characters in total: a Beefeater (aka a royal guard), the Dark Lady (referred to in Shakespeare’s famous sonnets), Queen Elizabeth I of England (the ‘Virgin Queen’), and Shakespeare himself.

It’s circa 1599. All prepared to meet his love who works at the royal palace, Shakespeare accidentally meets a sleepwalking queen instead. The poet’s real love, the Dark Lady, soon arrives and begins to berate the two figures who are partially shrouded in darkness. There’s a brief scuffle and two of them fall to the ground. Apologies and pleas for mercy quickly follow when the maid recognises the queen. Off with her head!

This little play artfully deflates the hero worship of William S. prevalent in the last few centuries. Shaw provides an extensive introduction to the piece, explaining its original inspiration and shedding some much-needed shade on our staid opinions about Shakespeare (“A very vile jingle of esses,” indeed!). The core theme of the piece is irreverent humour.

Ways to access the text: reading/listening

I sourced this text via Scribd. It’s also widely available on the internet.

An audiobook version is available on the Internet Archive, entitled “George Bernard Shaw: A BBC Radio Collection.” This is free, but I found the type of delivery a little formal at first. It didn’t quite meet my initial expectations of a farce, which seemed to be more in the style of Laurel and Hardy, and brilliantly so, rather than a Royal Shakespeare Company performance.

Why read/listen to Dark Lady of the Sonnets

It’s quite meaningful for students who have ponderously and adoringly poured over lines in Shakespeare’s plays when Shaw suddenly bursts that over-inflated bubble. The feeling of release from the shackles of obsequiousness is divine. Instead of the revered Bard, one gets an over-sexed, egotistical, pompous braggart whose main concerns are making money and a name for himself. This figure also has a faulty memory and jots down any clever sayings he hears. Yes, he’s a born plagiarist! The piece is quite slapstick, which works well when delivered in formal, Elizabethan-era English (surprisingly). Overall, it’s a fun sketch and worth discovering.

Post-reading discussion/interpretation

A Shavian Antidote to Bardolatry

George Bernard Shaw’s motivation for writing Dark Lady of the Sonnets was chiefly, though not exclusively, financial. Money was needed to establish a National Theatre. On the website of the present-day English National Theatre, one reads that “In 1848, London publisher Effingham Wilson was the first to call for a national theatre, in a pamphlet entitled ‘A House for Shakespeare.’” In other words, the project would prove itself to be a laborious and protracted one. Many crucial steps were needed before completion. For instance, in 1949 the government passed a bill releasing one million pounds of funding for the project. In 1951, Queen Elizabeth (the Queen Mother) laid the foundation stone, which turned out to be an amusingly premature move. Things finally began to gain momentum in 1962 when Laurence Olivier, the star of both film and stage, became Director of the National Theatre. He attracted new talent, took risks, and managed the project with obvious passion. Olivier witnessed the completion of the new building on the South Bank in 1973. Remember, Shaw’s little fundraising play is from way back in 1910.

The play itself is brief but quite funny. It has a Punch and Judy feel to it, but there’s more going on. In fact, reading the introduction to the piece, which is much longer than the play itself, alerts one to the issues at hand. Two key themes emerge: the argument behind the need for a national theatre, which is an artistic argument, and Shaw’s obvious beef with Shakespeare. The latter of these is far more entertaining.

It is best to begin with the sordid topic of coin! A national theatre is promoted as the chief means of releasing artists from the necessity of producing purely commercial works. In the play’s introduction, Shaw argues that Shakespeare knew that his best plays were never genuinely appreciated. As a sort of revenge, ”When Shakespear was forced to write popular plays to save his theatre from ruin, he did it mutinously, calling the plays “As You Like It,” and “Much Ado About Nothing” (Shaw 26). Shaw evidently disliked these two comedies. In the fictional meeting with Queen Elizabeth I, Shakespeare pleads for funding because the great British public will only pay for theatre tickets when there’s the promise of “a murder, or a plot, or a pretty youth in petticoats, or some naughty tale of wantonness” (40). Elizabeth’s practical response echoes centuries of civil servants who would follow her lead – “there be a thousand things to be done in this London of mine before your poetry can have its penny from the general purse” (41). The Bard’s chief argument is that the theatre has an educational, improving influence over the public. This argument has a familiar ring to it. And no, it didn’t work then just as it often doesn’t work now. The apparent need to fund ‘high culture’ while the mostly commercial, popular culture sector is left to its own devices is a tricky argument that gets more complex rather than less with each passing year. However, by imagining Shakespeare as an early proponent of the argument to publicly fund the arts, Shaw emphasises the dire predicament of all playwrights, past and present.

Apart from a plea to finance the arts, Shaw’s work doubles as a stupendous dig at Shakespeare himself. Ironic, since the funds are for a national theatre in the Bard’s own name. The Irish playwright’s fascination with Shakespeare was, of course, somewhat complicated. For instance, he fully appreciated that Shakespeare was a man of genius. In the introduction of Three Plays for Puritans, Shaw pays tribute to Shakespeare’s unique talent for depicting human weakness, writing that “his Lear is a masterpiece” (XXIX). On the other hand, such compliments contrast quite sharply with the summation of Shaw’s views as summarized in an article in The Folger Shakespeare Library, as follows.

“Shaw by 1906 was already famous for his own antipathy to the Bard. Take, for example, this diatribe, written in 1896:

‘There are moments when one asks despairingly why our stage should ever have been cursed with this “immortal” pilferer of other men’s stories and ideas, …’” (Ungenial geniuses)

Most readers are already familiar with the fact that Shakespeare found ‘inspiration’ for many of his major works from existing texts. The most obvious is Holinshed’s Chronicles, which was the base material for many of Shakespeare’s history plays. However, in the above quotation, Shaw describes the great poet as something more akin to a shameless plagiarizer. If Shaw could only read the 2018 article from The New York Times entitled “Plagiarism Software Unveils a New Source for 11 of Shakespeare’s Plays.” Technology normally used to catch cheating college students unearthed something much bigger – “two writers have discovered an unpublished manuscript they believe the Bard of Avon consulted to write “King Lear,” “Macbeth,” “Richard III,” “Henry V” and seven other plays.” It’s as if Shaw had a premonition when writing Dark Lady of the Sonnets. Here, Shakespeare is seen to copy down anything of interest on his writing tablet, be it a queen’s clever words or a Beefeater’s everyday observations. The magpie who collects shiny things is not concerned with ownership issues, nor was Shakespeare with copyright – apparently. Of course, the genius of Shakespeare was being able to re-mould such material into something great, and Shaw graciously acknowledged this too (Dark Lady 28). The ‘pilferer’ joke is still quite a zinger. It also puts an ironic spin on one of the famous lines in Hamlet – “Neither a borrower nor a lender be” (1-3-81).

There is a vein of gentle mockery that runs through all the topics already discussed. It’s lodged in the fact that it took over a hundred years to raise sufficient funds to build a single theatre in honour of the much beloved national playwright, whose works, incidentally, are taught in every classroom on the British Isles. There’s also a little cut at the poet when one learns that he had to churn out crowd-pleasing trash [according to Shaw] to keep the theatre doors open in Elizabethan days. Furthermore, Shaw asserts that many of Shakespeare’s great plays relied heavily on a gifted actor’s performance for their success. Richard Burbage was the star actor of Shakespeare’s day. The same rules apply today. For example, Andrew Scott, Jude Law, David Tenant, Maxine Peake, and Benedict Cumberbatch have all played [starred in] Hamlet since 2000. Ticket sales rely on a big name. Yet, the most cunning dig at Shakespeare is to depict him as a bumbling egotist who has a terrible memory and, therefore, jots down all sorts of potential literary trinkets. A sort of genius clown. All this leads one to consider the nature of the work that Shaw submitted to support the great Elizabethan tragedian. Yes, a crowd-pleasing comedy sketch! None of these things could be considered outright insults. Instead, they are like vigorous hammer thumps against the base of Shakespeare’s monumental status.

The play itself, Dark Lady of the Sonnets, is a well-executed piece of comedy writing. The character traits of Shakespeare that Shaw wishes to lampoon are several. Let’s run through them. First, the dark lady arranged to meet Shakespeare so that she could break off her relationship with him. Apparently, he’s an infuriatingly talented linguist who is either seducing her or insulting her – both with spectacular effectiveness – and she’s had enough already. Sonnet 130 is a fitting example; he says the Dark Lady has seriously unruly hair and her breath stinks too – “And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare / As any she belied with false compare” (lines 13-14). Shaw also depicts Shakespeare as pomposity personified – what with his family coat of arms; his father’s high name; his claim of making things immortal with only words; and his arrogance to attempt seducing the virgin queen. The Shakespeare one meets in the sketch is amusing, but he’s unlikely to be someone whose company you’d ever seek.

However, Shaw’s caricature of the Bard has a specific backstory. Trey Graham explains the situation as follows and he references the self-explanatory term of bardolatry.

“His [Shaw’s] utter impatience with “Bardolatry”—his efficiently dismissive coinage for the breathless Victorian fanboying that elevated Shakespeare to the ranks of the prophets and the philosophers—that impatience would remain with him to the grave.” (Graham)

Shaw could see flaws in Shakespeare’s work, and he simply wished to bring about a more balanced view of this historical, literary figure. Humour works toward regaining this proper balance. Shaw won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1925 and then in 1939 he added an Oscar, which was for the screenplay of Pygmalion. In other words, few writers were as qualified as Shaw to critique Shakespeare. That said, Shaw asserts that “It does not follow, however, that the right to criticize Shakespear involves the power of writing better plays” (Puritans XXXI). Therefore, more common readers should beware of the label of ‘great writer’ that is attached as a stamp of quality to certain names like Shakespeare’s. All of us should be willing to trust our own judgements – once we are literate and have read at least one other book.

“Do not be misled by the Shakespear fanciers who, ever since his own time, have delighted in his plays just as they might have delighted in a particular breed of pigeons if they had never learnt to read.” (Puritans XXX)

It would also be possible to analyse the play with reference to the famous Shakespeare sonnets on which the story is based. Was the Dark Lady really Mistress Mary Fitton? (google her and see the famous painting). Who was the fair youth, William Herbert? However, C. L. Barber warns that “The who, where, when are beyond knowing, despite the tantalizing closeness of the poems to Shakespeare’s personal life” (648). There are just over 150 sonnets in total and a vast array of literary heavyweights have commented on them, over several centuries. It’s a daunting field of study. One crucial point is that the only person Shakespeare ever immortalized through these poems was himself. Neither his mistress, the Dark Lady, nor the man he loved (platonically or romantically) are ever named. Not even initials in dedications seem to help. It’s also out of step with the light tone of Shaw’s irreverent piece to begin a thoughtful analysis. Having done some research into the sonnets about whether they say anything definitive about Shakespeare’s personal relationships, I found a rabbit hole of preposterous proportions.

Shaw’s Punch and Judy show starring one of history’s most famous threesomes – Elizabeth I, Shakespeare, and the Dark Lady – is meant as unadulterated entertainment. Akin to a carnival festival when one may don a wacky costume and act completely out of character, we see revered figures play-acting for our amusement. For an audience, the pleasure rests in the witty dialogue and in recognizing lines from various Shakespeare plays like Hamlet and Macbeth. Shaw sought to make a point, and he does it well: beware of revered figures and dare to poke fun at them now and again.

Works Cited

Barber, C. L. “Shakespeare in His Sonnets.” The Massachusetts Review, vol. 1, no. 4, 1960, pp. 648–72. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25086565.

Blanding, Michael. “Plagiarism Software Unveils a New Source for 11 of Shakespeare’s Plays.” The New York Times, 7 Feb. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/02/07/books/plagiarism-software-unveils-a-new-source-for-11-of-shakespeares-plays.html

Graham, Trey. “George Bernard Shaw on Shakespeare.” Folger Shakespeare, 1 May 2018, www.folger.edu/blogs/shakespeare-and-beyond/george-bernard-shaw-on-shakespeare/

“Our History.” National Theatre, Our History – National Theatre

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet, The Folger Shakespeare, www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/cite/

Shakespeare, William. “Sonnet 130: My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun.” Poetry Foundation, http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45108/sonnet-130-my-mistress-eyes-are-nothing-like-the-sun

Shaw, George Bernard. Dark Lady of the Sonnets, Sovereign, 2018.

Shaw, George Bernard. Three Plays for Puritans, Grant Richards, 1901.

“Ungenial geniuses: Shaw on Shakespeare.” Folger Shakespeare Library, http://www.folger.edu/blogs/shakespeare-and-beyond/george-bernard-shaw-shakespeare-ungenial-geniuses/