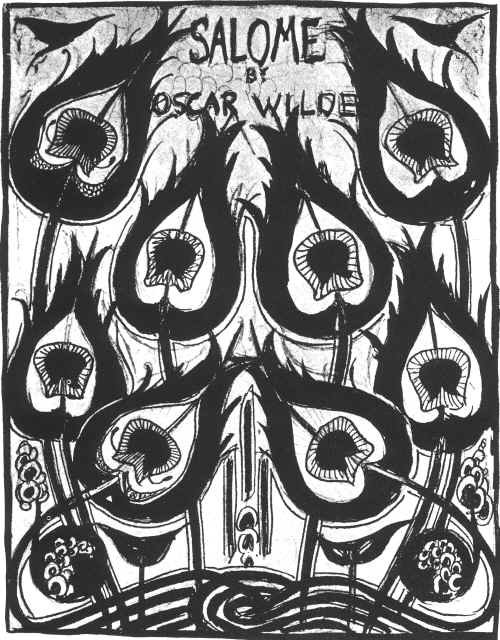

Sketch for cover design of Salomé by Aubrey Beardsley. 1894.

- Play Title: Salomé

- Author: Oscar Wilde

- Written (in French): 1891

- First published in English: 1894

- Page count: 65

Summary

Salomé is a one-act play by Oscar Wilde that is based on the biblical story of John the Baptist’s death. Wilde uses considerable poetic license in his version of what was originally a story from the gospels of Saints Matthew (14:1-12) and Mark (6:14-29). The play’s setting is the palace of Herod, and the occasion is a banquet to entertain the ambassadors of Caesar. John the Baptist is a prisoner of Herod. In brief, Salomé, who is the stepdaughter of Herod, asks for the head of John the Baptist because he has shunned her romantic advances. This tale of beheading is well known, as is the dance of the seven veils that Salomé performs. What makes Wilde’s play quite distinctive is the emphasis on symbols, most notably the moon. It is also a decadent piece of literature that focuses on the transgression of moral and sexual boundaries. Indeed, the play was originally banned in England as it ostensibly dramatized a biblical tale, but more likely due to the risqué content of the play. The artist Aubrey Beardsley supplied sixteen, now-famous illustrations to accompany the text.

Ways to access the text: Reading/listening

The full text of the play is available on Project Gutenberg and includes the illustrations by Beardsley. There are multiple uploads of the text on Gutenberg, but a search for “Salomé: A Tragedy in One Act by Oscar Wilde” will return one of the English language versions.

If you would prefer to listen to the play as an audiobook, then I would highly recommend a version available on YouTube entitled, “Salomé by Oscar Wilde – Lester Fletcher.” The running time of this audiobook is 49 minutes so please note that this is an abridged version. However, it is also a professional production and preferable to the many amateur recordings online.

Why read/listen to Salomé?

A femme fatale

Most people are at least vaguely familiar with the story of Saint John the Baptist, and the notorious woman who asked for his head on a silver platter. In fact, this biblical story was extremely popular in the 19th century, especially amongst French writers, so Wilde was not alone in rewriting the tale. However, Wilde depicts Salomé as an especially powerful, narcissistic, dangerous woman who oversteps so many lines that she finally shocks the reader. It is important to note how different Wilde’s Salomé is from the woman in the original biblical story. In the original, Salomé is merely Queen Herodias’ daughter and is not even named in the text; moreover, she only requests the head of John the Baptist because it is her mother’s wish. In Wilde’s play, Salomé is transformed into a far more assertive figure who is aware that her royal status and sexual allure may be used as tools to impose her will upon others. A femme fatale who originates in a bible story is certainly unusual, but the label is appropriate because Wilde depicts a woman whose actions cost the lives of two men and the ruination of a third. Few people want to read a story where the ending is already known. Therefore, it is important to point out that the moment of true depravity in Wilde’s play, the ghastly crescendo moment, is not the execution of the Saint!

Wilde’s command of language

Reading or listening to Salomé is a distinctive experience due to how Wilde has crafted the language of the play. This work is quite dissimilar to his more popular, comedic plays, for example, The Importance of Being Earnest. One should certainly not approach Salomé expecting light comedy or wit. It is best to emphasize that this play is symbolist in nature, and the key symbol of the moon could even be said to have its own role. Wilde also focuses on a few particularly symbolic colours in the work. Additionally, his style includes the superfluous use of similes. These observations are not made to dissuade the potential reader but to underline that Wilde creates a heady, artificial environment where the language seems laboriously ornate at times, packed with symbols, and purposely repetitive in nature. However, once one begins to appreciate the effect that the author is striving to achieve then one does not resist the language merely for being slightly unfamiliar. What the author undoubtedly achieves in the play is the steady ramping up of tension. This work is tragic, and the author creates an atmosphere of impending doom in language that perfectly reflects his own aesthetic style. Due to the unfamiliar style of language and the often elaborate and detailed descriptions of things, the reader may indeed begin to feel mesmerized. This wondrous effect is purely a consequence of Wilde’s astonishing command of language.

Post-reading discussion/interpretation

The Moon’s Significance

The moon is a prominent symbol in Wilde’s play. In ancient times, the Greeks worshipped the moon goddess Selene while the Romans had an equivalent goddess named Luna. The moon has long been a symbol of womanhood, and special rites accompanied the arrival of the new moon and full moon. In the opening lines of Salomé, the descriptions used by the young Syrian and the Page of Herodias serve to conflate the princess Salomé with the pale moon in the night sky. Wilde uses this literary device to highlight the importance of the moon as a primary symbol and to immediately link it to Salomé. However, the central question is what the moon signifies in the play. In this regard, Wilde’s main symbol appears strangely unstable because each character sees something quite different in the moon. The Page of Herodias ominously sees a “dead woman” who is “looking for dead things,” whereas his young friend, the Syrian, sees “a little princess who wears a yellow veil.” Herodias remarks nonchalantly that “No; the moon is like the moon, that is all,” but she warns that those who look too long upon it may go mad. It is significant that Salomé self-identifies with the moon. She tellingly describes it as “cold and chaste” and says, “I am sure she is a virgin.” It is easiest to interpret this alliance between Salomé and the moon as being indicative of her influential power over others. Salomé wields power whereas the other characters, who find highly subjective meanings in the moon, are by contrast quite vulnerable to influence. According to the key tenets of the symbolist literary movement, symbols were richly suggestive rather than explicitly restricted to one meaning. When Wilde employs the moon as a symbol, he makes it aesthetically beautiful but without any true depth. The moon has a mirror surface that will not reveal its true meaning. Similarly, Salomé hides her true character while others tend to project qualities onto her, which are just projections of their own fears and desires. The use of the moon as a symbol communicates that Salomé is a perpetually mercurial figure, an enigma. It is necessary to delve deeper into the play to comprehend this strange figure.

Another aspect of the moon symbol is the significance of colours, specifically white, red and black. Wilde makes numerous references to these colours, so it is best to reduce an interpretation to the most essential points. For instance, Iokanaan (John the Baptist) declares a key prophecy, saying, “In that day, the sun shall become black like sackcloth of hair, and the moon shall become like blood.” The day he prophesizes is the day when the “daughter of Babylon” (Salomé) shall die, crushed beneath the shields of soldiers. Herod later recalls this prophecy, just before Salomé dances, when he notices how “the moon has become as blood.” To aid one’s overall understanding, one must note that the colours white, red, and black each symbolize specific things in the play. White is associated in the play with doves, flowers, butterflies, and snow; it is a symbol of purity and chastity. Red is associated with wine, blood, fruit, and lips; it is symbolic of sexuality. Finally, black is associated with the cistern/hole where Iokanaan is imprisoned, with the executioner, Naaman, who is described as a “huge negro,” and with the “huge black bird.” Black is, therefore, symbolic of death. Many critics divide the play into sections that correspond with particular phases of the moon, which in turn correspond with the predominance of each of the aforementioned colours. The changing colours highlight the ever-changing perceptions of Salomé. As such, the play opens with a pale, chaste, young princess. Then, after Narraboth’s blood is spilt, we enter the red phase; the moon changes colour and Salomé performs the sexual, erotic dance of the seven veils. Finally, we enter the black phase when Herod orders that all lights be extinguished, and the princess dies.

The moon’s significance is ultimately determined by the power that each character attributes to it. Only Queen Herodias, Salomé’s mother, is immune to the influence of the moon. Herod, however, is sensitive to omens of any kind – most notably the changing colour of the moon, He is also the only character who receives the same premonitions as Iokanaan. The most significant premonition is the coming of death which is first signalled to Iokanaan when he hears “the beating of the wings of the angel of death.” Herod also hears the same “beating of vast wings.” The key question is whom Death has come to retrieve for the netherworld? Since Herod is quite fearful of the prophet Iokanaan, he first concedes that his marriage to Herodias is incestuous. Herod is now willing to appease the wrath of the prophet’s God. It may seem odd that Herod, who views Caesar as the “Saviour of the World,” rather than Jesus, is the one to carry out Iokanaan’s cruel sentence on Salomé (crushed beneath soldiers’ shields). Yet, this is how prophecy, fear, and the moon’s symbolism are brought into alignment in the story.

Wilde constructs an intricate plot. For instance, Herod twice removes the veil from a precious symbol. Symbols have already been shown to be unstable so tampering with symbols also carries a definite risk. In the first instance, Herod steals the sacred veil from the Jewish temple and thereby potentially removes all mystery from a sacred object. The second occasion is when he requests that his stepdaughter perform a dance: a dance where she removes seven veils and transforms her identity from a chaste, virginal daughter to a potential future wife. Herod reveals his lurid fantasies about Salomé, but they are expressed obliquely through his comments on the moon’s appearance. He says ‘she’ (the moon) is a naked, drunken woman “looking for lovers.” In the last moments of the play, the moon reflects her light upon Salomé and reveals the girl’s true identity, namely a depraved necrophiliac. This shatters Herod’s plans to take his stepdaughter as his future wife. Herod is confronted with an obscenity and immediately fears reprisals from the prophet’s God, so Herod must sacrifice Salomé. It is fitting that Herod had previously cautioned, “It is not wise to find symbols in everything that one sees. It makes life too full of terrors.” It is Salomé’s downfall that King Herod interprets the moon as a symbol of what Salomé can become: his new wife. When the king’s initial interpretation is proven wrong, and the moon is blood red, and the prophet’s words of warning ring in the king’s ears, then Salomé must die.

The moon orbits in the heavenly realm, tugging upon the tides of vast oceans and men’s hearts too. The metallic shine on her brow protects her from man’s ire, regardless of his atrocious fate. Salomé believed that she would also reign with such untouchable aloofness, but she found that she was just a mortal girl. True to the symbolist literary movement, Wilde shows how unstable and ultimately dangerous symbols can be. King Herod looks upon the moon and what is reflected back is the dark sin within his soul.

Looking is Dangerous

Wilde depicts the ‘male gaze’ in all its sleazy splendour through the character of Herod. Yet many characters become obsessed with others’ appearances in the play. Herod and the young Syrian stare unashamedly at Salomé, and, in turn, Salomé stares wantonly upon Iokanaan. It also seems that the Page of Herodias stares too intensely at Narraboth (the young Syrian) while warning him, “You look at her [Salomé] too much … something terrible may happen.” In modern language, the situation becomes quite meta. Wilde depicts lascivious men looking at a girl, a lascivious girl looking upon a grown man, and a sexually jealous young man looking at his male friend. Therefore, the act of staring is not hindered by issues of gender or even sexuality. Each character projects their own personal longings upon what becomes a mere object of desire. The various persons being stared at are translated into mere surface and thereby instantly robbed of their full personalities. Most notably, Iokanaan the prophet is shamelessly reduced to superlative descriptions of his body, hair, and lips by Salomé. The prophet’s core message including his religious chastisements falls on dumb ears. Salomé simply says, “I am amorous of thy body.”

Staring induces fear because it reveals a disregard for hierarchy (Narraboth, a slave, desires a princess), or it reveals a transgression of the law of Moses (Herod’s sexual desire for his stepdaughter). It is noteworthy that those who chastise the ‘starers,’ namely Herodias and her Page, each have something to lose. Herodias may lose her crown and half a kingdom to her own daughter while the Page may lose the special friend whom he has showered with romantically charged gifts (perfume and rings). Moreover, the stare isolates characters from one another because what is visually appealing or tantalizing has the consequence of muting all warnings: leaving language impotent. All things become surface alone, and as the play reveals, such looks can be highly deceptive.

We comprehend that a stare reduces the looked-upon-person to a mere object. What makes staring unusually dangerous in Wilde’s play is just how far characters will transgress societal norms to attain an object of desire. In this regard, Salomé herself is unmasked as truly monstrous. In comparison, Herod’s sexually motivated gaze may be called traditional as it is camouflaged with enticements to Salomé to yield to his will. His initial order to dance soon becomes a sugared plea with promises of jewels and half a kingdom. In bleak contrast, Salomé’s will to fulfil her desires is steely, and she offers Iokanaan nothing in exchange for his cooperation. The prophet forcibly rejects her lurid advances, saying, “I will not have her look at me,” and he prefers to return to his prison cell rather than endure her obscenities. Iokanaan’s belief that a mere look is wounding echoes the mythology of Medusa. Salomé destroys this man of God just so she may experience the kiss she hungrily desires. If one heeds Herod’s wise words, then looking reveals an inner truth. In the final scene, the girl that Herod most desires is revealed to be a monster, and he says, “I will not suffer things to look at me.” Wilde daringly reveals the power of a sexualized stare, especially when it is ironically reversed and suddenly shocks.

Works Cited

The Bible. Authorized King James Version, Oxford UP, 1998.

Wilde, Oscar. Salomé, A Tragedy in One Act. Translated by Alfred, Lord Douglas, Project Gutenberg, 2013.