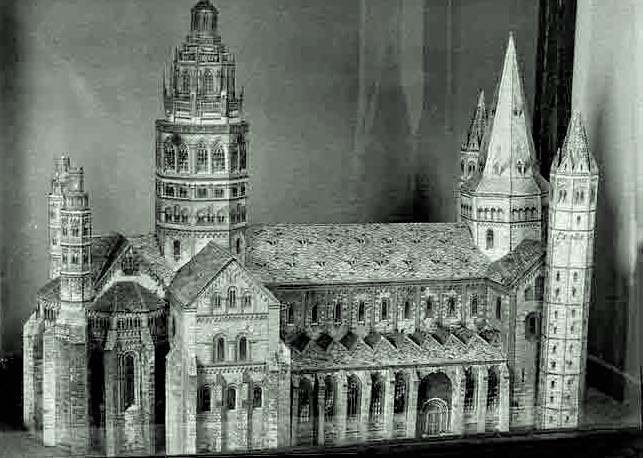

Joseph Carey Merrick’s model of St. Phillip’s church.

- Play title: The Elephant Man

- Author: Bernard Pomerance

- Written/first printed: 1979

- Page count: 70

Summary.

The Elephant Man by Bernard Pomerance tells the story of a person who suffered from a medical disorder that progressively disfigured him. The play is based on the true-life story of Joseph Carey Merrick from Leicester who died aged 27 in the year 1890. The focus of this drama is the transformation of Merrick’s life brought about by the support of Dr Frederick Treves of the London Hospital. Merrick initially made his living as an exhibit in various freak shows in London and Brussels before his move to the London Hospital as a permanent resident. This play may be viewed as a historical drama since it explores the meaning of benevolence in late Victorian London and what effects charity and care had on a recipient such as Merrick. The central theme is normality and how it may or may not be achieved.

Ways to access the text: Reading/watching.

The play script is available online via the Open Library and various other sources.

The play is reader-friendly, however, if you do wish to watch it then the recommended version closest to the original play is a TV movie from 1982 entitled The Elephant Man, which is available on YouTube. This is different from the film version starring John Hurt released in 1980. Pomerance makes an interesting comment in the introductory note to The Elephant Man – “any attempt to reproduce his appearance and his speech naturalistically – if it were possible – would seem to me not only counterproductive, but, the more remarkably successful, the more distracting from the play.” It is important to keep this advice in mind if you do choose to view rather than read the play.

Why read The Elephant Man?

Dramatization of a true account.

It seems cliched to recommend a work because it is based on a true story. However, Merrick’s medical condition was so unusual that a replica of his skeleton is still on display in the museum of the Royal London Hospital. Famous books on Merrick include one by his physician, Dr Treves, and one by Ashley Montagu. These texts form the basis of the biographical information for Pomerance’s play. It is relevant for a reader to appreciate that Merrick was a real man with a horrible condition because it adds pathos to the story. Merrick’s condition was formerly thought to be neurofibromatosis but is now believed to have been proteus syndrome. The most striking symptom was bodily disfigurement that consisted of excessive growth of skin and bone in various parts of the body. This left Merrick’s face looking almost alien, made speech quite difficult for him, and facial displays of emotion almost impossible. The circumference of his head measured almost three feet (1 metre) by the time of his death. When one reads the play, it becomes apparent that empathy has a vital role, yet its absence is repeatedly depicted. Knowing that this is a true story makes one consider Merrick’s horrible predicament. He was born a seemingly normal child, but his medical condition later revealed itself and got progressively worse. As true stories go, this one is quite exceptional.

Death by benevolence.

Pomerance’s play scrutinises the concepts of personal and societal benevolence and what underpins such attitudes. Upon reading many summaries of this play, one would initially presume that Merrick is saved by Dr Treves either by some medical intervention or through basic kindness and support. Paradoxically, neither of these presumptions is wholly wrong, yet the drama reveals something unexpected. What a reader learns is that Merrick and Treves have almost equal influence on each other, and this is dramatized in their sometimes uncomfortable and challenging interactions. This is not a saccharine tale of how a doctor received a life lesson from a deformed patient; it is an investigation into the often positive but sometimes detrimental results of interference in another’s life. It is up to the reader to decide what eventually kills Merrick. Could it possibly be kindness?

Post-reading discussion/interpretation.

Exploitation disguised as charity.

John Merrick, as we meet him at the play’s opening, is struggling to maintain independence in the most adverse of conditions. He performs in freak shows to earn money and consequently suffers “humiliations, in order to survive.” When he is in Belgium with his manager, Ross, he says, “In Belgium we make money. I look forward to it. Happiness, I mean.” Unfortunately, Ross soon discards Merrick when it is no longer possible to obtain a performance license. Ross additionally robs the deformed man’s life savings. In an ironic twist, Dr Treves had already met John Merrick before this failure in Brussels. Treves had paid Ross “5 bob” for John’s services in London. On that occasion, John was displayed like an exhibit in front of anatomy students, which does not indicate any compassion or empathy on the doctor’s behalf. Indeed, it was because of the disgust of one of Dr Treves’ anatomy students, having learned about how John worked in a freak show, that John had to flee from England. In this light, ever before Dr Treves dramatically comes to the rescue, a reader is fully aware of his less-than-honourable past actions. Upon returning to London from Belgium, Merrick is penniless and vulnerable to an imminent attack from a public mob when he unexpectedly meets Dr Treves for the second time. Merrick, the man who long strived for independence, has been reduced to begging, saying “Help me!” This abject vulnerability is arguably exploited by Dr Treves and the London hospital.

One may say that Merrick has simply changed masters, from Ross to Treves. For example, Gomm’s letter to The Times newspaper eventually results in sufficient funds “that Merrick may be supported for life without a penny spent from hospital funds.” Yet, Merrick is still held to a contract of sorts, which he mentions in passing to Mrs Kendal. The unwritten contract is not unlike his old contract with Ross: a contract to perform. Under the new contract, Dr Treves expects Merrick to stringently observe the rules. The patient is explicitly made to repeat the phrase “If I abide by the rules I will be happy.” Dr Treves proclaims that he and the hospital will provide “normality” for Merrick. However, they strive instead to make him normal. The demands on Merrick include practising polite conversation, welcoming affluent and influential guests, and responding positively to Treves’ expectations.

It is necessary to consider the financial aspects of Merrick’s situation. Just as Ross once described Merrick as financial “capital,” Gomm similarly says of Merrick, “he knows I use him to raise money for the London” (hospital). Therefore, Dr Treves’ benevolent actions not only improve the reputation of the hospital, but they result in a financial windfall too. Meanwhile, the doctor publishes several successful papers on Merrick’s medical condition. When Ross returns with a new financial proposition for the quite transformed Merrick, he cynically observes, “You’re selling the same service as always. To better clientele.” Ross once proclaimed Merrick to be a “despised creature without consolation,” This perverse, promotional slogan appealed to the freak show audiences that paid tuppence per ticket. Much later, Gomm addresses a letter to the charitable donors of the hospital to inform them of Merrick’s death, a letter to be published in The Times newspaper. This letter is a true insult to Merrick because Gomm, like Ross before him, manufactures a message that the benevolent public will most gladly consume. The text reads that Merrick “quietly passed away in his sleep” and thus conceals the unsavoury truth that he died of asphyxiation! As such, Merrick is still regarded as “capital.” The paying public must be given what they most desire, namely a feel-good tale, and in return, they will open their wallets and purses.

It is not reasonable to assert that Dr Treves sets out to exploit Merrick, but it is nevertheless the unfortunate, final result. Financial exploitation is a key issue, but it goes further than that. The two dream sequences of Dr Treves show his own facility for self-criticism, and this is a turning point in the story since the main authority figure realises his mistakes. In one dream, Dr Treves and Merrick undergo a reversal of roles, and Treves is exposed to the callous style of treatment he formerly doled out. Standing before a gawking audience, Dr Treves’ normality is coldly observed and critiqued, including his “vision of benevolent enlightenment.” This vision of Treves has its foundations in Victorian morals and the certainties of a great imperialistic power such as England was at the time. The strongest criticism from Merrick is that Treves is “unable to feel what others feel, nor reach harmony with them. This echoes Merrick’s earlier criticism when the porter, Will, was fired by Treves and Merrick said, “If your mercy is so cruel, what do you have for justice.” Treves was indeed devoid of empathy for Merrick’s situation and went about crudely moulding him into a “normal man,” remaining insensitive to the myriad psychological costs. The final interpretation must be that Dr Treves’ prescribed form of normality is deeply oppressive and leads to the cruel exploitation of Merrick rather than his salvation.

The church-model metaphor.

There are several remarkably interesting images and allusions that are repeated throughout the play: the model of St. Phillip’s Church, women’s corsets, and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. However, it is not possible to consider all of them due to the desired brevity of this discussion, so only the church metaphor will be considered here.

Pomerance’s introductory note to the work states that “the church model constitutes some kind of central metaphor, and the groping of conditions where it can be built and the building of it are the action of the play.” Once Merrick has seen the real St. Phillip’s, he concludes that “it is not stone and steel and glass; it is an imitation of grace flying up and up from the mud.” In this respect, his church model is an imitation of an imitation as Merrick himself says, and Treves adds that Plato had a similar theory. Indeed, the play presents several episodes where illusion conflicts with reality. To start to unravel the meaning of the church model, one must begin with a working definition of what Merrick means by grace. In its religious sense, a dictionary definition would explain grace as, ‘the unearned favour of God.’ It could also mean ‘elegance of movement’ if one considers the architectural beauty of a church spire reaching high into the sky. In both of these respects, poor Merrick is lacking. He has been made in the image of God, but he quips, “he should have used both hands shouldn’t he” meaning that God did him no favours. Merrick also has a pronounced limp, so he possesses no grace of movement. If the church model is a guiding metaphor, then Merrick is striving to either find or create an environment where he reaches some form of grace. His unfortunate starting point is his painful consciousness of his own incompleteness, his flaws, and his perceived need for transformation.

In the action of the play, Merrick’s gradual completion of the church model parallels his own improvements in speech and manners. At the conclusion of several scenes, he adds yet another piece to the model. It is most significant that Merrick adds the final piece after Dr Treves breaks down and must be consoled by the bishop. Treves compares himself to a gardener who has manipulated nature. He has “pruned, cropped, pollarded and somewhat stupefied” all that is under his care. Dr Treves experiences a crisis because he has made Merrick “dangerously human,” meaning that he has robbed his patient of his unique identity. Treves says, “We polished him [Merrick] like a mirror, and shout hallelujah when he reflects us to the inch.” It is tragic because Merrick was all too willing to conform to the demands of his taskmaster in a desire to reach the elusive status of normality. The “Elephant Man” followed all the rules in a desperate attempt to fit into his new home, and now it seems that the man who decided the rules, Treves, had been wrong all along. The play ends with Merrick’s strange dream of the Pinhead ladies who sing, “Sleep like others you learn to admire.” Merrick had always slept in a sitting position, which was safe for him, so his tragic attempt to sleep like a normal man is the cause of his death. The changes that Merrick hoped would transform him into a man like all others, including his striving for grace, led him on a path of self-destruction. The construction of the church model serves as a foil for his disillusionment. Merrick pursues a model of living normally that betrays him and finally kills him.

Works Cited.

Montagu, Ashley. The Elephant Man, A Study in Human Dignity. Acadian House Publishing, 1971.

Pomerance, Bernard. The Elephant Man. Grove Press, 1979.

Treves, Frederick. The Elephant Man, And Other Reminiscences. Cassell and Company Ltd., 1923.