Davis, Frederick William. As You Like It, Act II, Scene 7. 1902, Warwick Shire Hall, Warwick.

- Play Title: As You Like It (All the world’s a stage)

- Author: William Shakespeare

- Written: circa 1598

- Page count: 58

Summary

As You Like It is one of William Shakespeare’s most celebrated comedies. The play is set in France where Duke Frederick has recently usurped his brother (Duke Senior). Rosalind, the outcast Duke’s daughter, remains at court since she is best friends with Celia, who is Frederick’s daughter. One day, Rosalind watches a public contest between the court wrestler and a young man named Orlando. She instantly falls in love with the brave Orlando. This young man has been disinherited by his older brother Oliver, and he subsequently flees to the Forest of Arden due to his brother’s ongoing vendetta. When Rosalind is unexplainably banished from court, she too flees to the forest accompanied by the ever-loyal Celia. For safety, Rosalind disguises herself as a man and calls herself Ganymede while Celia takes on the new name of Aliena. Orlando then meets Ganymede (Rosalind) and they become friends. Ganymede promises to ‘cure’ Orlando of his love for Rosalind. Comedic encounters ensue. The play concludes with multiple marriages and renewed peace at court.

Rather than look at the entire play, the short essay in this post will address only Jaques’ famous monologue that begins with the line – “All the world’s a stage” (AYL 2.7.146).

Ways to access the text: reading/listening

The play is easy to find online. For example, one may read the full text on The Folger Shakespeare website.

Many free audiobook versions have been posted online. One example is a recording from 1962 starring Maggie Smith as Rosalind. It can be found on the Internet Archive website under the title “Living Shakespeare: As You Like It.”

There are a few movie versions of the play. To start, there is Kenneth Branagh’s As You Like It (2006). Alternatively, one may search for “‘As You Like It’ at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre,” which is a recording of a live stage performance. This receives a rating of 7.7/10 on the IMDB website

Why read/listen to/ watch As You Like It?

It’s probably acceptable to say that As You Like It (AYL) is a frothy, early-modern period comedy that has aged reasonably well. Few plays have lines like Rosalind’s, aka Ganymede – “Love is merely a madness; and, I tell you, deserves as well a dark house and a whip as madmen do” (AYL 3.2.407-409). No, the play does not veer into Fifty Shades of Grey territory, but it’s full of Shakespeare’s familiar witticisms and wordplay. Of particular interest are the gender-bending antics where a boyish Rosalind gets an unsuspecting Orlando to woo her while she’s still in male attire. This is part of the ‘cure’ that Ganymede administers to Orlando to solve the problem of his unshakeable love for Rosalind (confused yet?). It’s a tale of love, disguises, feuds, reconciliations, and of course – lots of marriages. This play isn’t just for Shakespeare buffs, or students, because it delivers on several levels for modern readers.

Post-reading discussion/interpretation

Jaques in the Era of TikTok and Crack

Does As You Like It need a new interpretation? That is the question. ‘Probably not’ is the answer that immediately springs to mind. It’s not that I didn’t enjoy tackling some of Shakespeare’s weightier plays in the past, but comedies are far trickier. They dissolve into nothingness quicker than wet tissue paper when one tries to analyse them. It’s probably because humour doesn’t normally need to be dissected; it hits the spot, or it doesn’t. AYL is a play you possibly studied at school, or maybe at college, or maybe you saw the Kenneth Branagh film version. The wordplay is fun, and the jokes are witty, but few people need a detailed interpretation of the pastoral world evoked in the Forest of Arden. By comparison, some of Shakespeare’s other comedies like A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Twelfth Night are meatier and can endure a pernickety analysis quite well. Alas, it is the fate of AYL to be mercilessly dissected by either semi-illiterate 14-year-olds or those with doctoral degrees. For me, it is sufficient to look at a single, famous monologue from the play and try to imagine what it means for a modern-day reader. The speaker’s name is Jaques who is a Lord attending on the exiled duke. This Jaques probably had a life quite different from, let’s say, a present-day, twentysomething Data Analyst from Dagenham, or Dijon (keeping it French). Yes, people go through the same stages of life as described in the monologue, but it must be different, surely. This essay will look at a few of those differences.

To begin, this is the monologue from the play.

Jaques: All the world’s a stage,

(AYL 2.7.146-173)

And all the men and women merely players.

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

Then the whining schoolboy with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honor, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side,

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

(L) Photo of the reconstructed Globe Theatre of Shakespeare. (R) Escher, Maurits Cornelis. Eye.1946.

Shakespeare’s conceit that life is like a play seems far less of a novel comparison today than it may have been in the late 16th century. It’s unsurprising that Shakespeare, an actor and public persona, considers one’s time in the glare of the public eye as real living. In those days, the only ‘famous’ people were rulers, philosophers, adventurers, artists, inventors, and villains. Actors played these parts on stage and thereby got a taste of the adulation by proxy. Fame was hard-earned, inherited, or gained for all the wrong reasons. Ordinary people were mostly invisible by comparison, merely an audience in waiting. There was no fast track to celebrity or infamy. Fast forward to the 21st century, and everyone can reach a dubious level of fame. The reason is simple – the eyes of the small audience within the Globe Theatre in Shakespeare’s example have been transformed into the all-seeing eye of modern life. Just consider for a moment that there are CCTV cameras on practically every street corner and inside most public buildings today. Even if you go off the grid, you can still be photographed from space regardless of the obscure location. Anyone with a smartphone and fingers (yes, the bar is high) can film events as they happen and save them for sharing later. Do the wrong thing in public and fame/infamy can be foisted upon you.

Private individuals can also participate in ‘broadcasting’ their lives. Think of platforms like X, TikTok, Facebook, and YouTube. In 1968, Andy Warhol predicted that “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes” (NPR). For a decidedly darker take on the future, George Orwell’s 1949 dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four warned that “Big Brother is watching you” (1). Little did the author know that modern society would actively embrace such unremitting surveillance with greedy, clasping arms. Marilyn Monroe wasn’t alone in knowing how to make love to the camera. In short, Shakespeare’s idea of the world as a stage was incredibly prescient. All our lives have started to play out in a public arena, regardless of our wishes. Videos on everything from sex to suicide are posted online and an ever-ready global audience of eager watchers will ceaselessly click on them. But to get some perspective – I’d still prefer to post an unintentionally embarrassing TikTok video and figuratively die of shame rather than die (anonymously) of the bubonic plague back in William’s day.

Shakespeare’s seven ages of man begin, uncontroversially, with infancy. “Mewling and puking” doesn’t strike one as ideal, but it’s actually not as bad as it sounds. Mewling is like the sound of a kitten in a box – a soft yet high sound. The puking part is quite normal too, so let’s not call a social worker yet. Instead, let’s delve a bit further. The kid is in a nurse’s arms, not its mother’s. This doesn’t mean a hospital setting but refers to a wet nurse: a woman whose occupation was to care for and breastfeed the child. Wet nurse was a bone fide job title in Tudor England. Being a wet nurse in Shakespeare’s day is probably like being a techie today, i.e. guaranteed employment. In fact, not until the Industrial Revolution did society see the widespread introduction of baby bottles and the all-important infant formula to put in those bottles (Martins). Therefore, breast milk was the only option for these Shakespearean-era babies. Indeed, such infants were often breastfed for two whole years with the slow introduction of soft foods at the latter end of this period. In Catholic England, these wet nurses did fairly okay, but with the Protestant Reformation came some decidedly bad press – “Protestant writers often described wet nurses as ‘drunkards’, ‘sluts’, or ‘gossips’” (Martins). The character of the wet nurse was crucial because, at that time, breast milk was believed to actually shape the character of the child. The Scientific Revolution was in its own infancy at this point in history, so let’s cut it some slack and simply compress the science into the slogan of ‘bad boob equals bad baby.’ The Tudor English did, however, know that breastfeeding is a natural contraceptive: women normally don’t return to fertility until they’ve stopped. Therefore, maybe some wet nurses had the opportunity to be bad, so to speak, and the rest just got a bad name. On the other hand, who wouldn’t turn to hard liquor after two years of breastfeeding? How does this relate to modern-day scenarios? Well, Erasmus famously said that “a mother who doesn’t breastfeed only deserves to be called “half-mother” by her offspring” (Folger). Well, there you have it from the esteemed philosopher’s mouth. Mothers are always wrong is the clear motto. This particular gospel has been in vogue since at least Medieval times. In the last century, we have somehow managed to add pop psychology to the mix, so the rights and monumental wrongs of motherhood have become even more debated.

There’s a definite theme within Shakespeare’s phases of childhood since the schoolboy is next and he’s eternally “whining.” This is the familiar ‘woe is me’ stage of childhood that many parents dread. However, Elizabethan England had no compulsory national system of education, so only privileged kids got to go to school. Well, maybe privilege is the wrong word since schoolmasters of that era had a penchant for using birch rods to punish dunces, daydreamers, ne’er do wells, and … everyone really. It was, quite frankly, the preferred implement of torture. Also, the children who made it to grammar school would be in class at 6 am and not finish until 4 or 5 pm, phew.

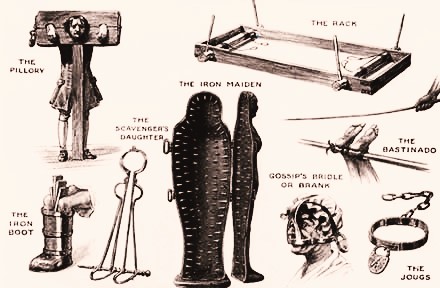

England was generally a more severe society in those days with public punishments being nothing unusual – “Vagrants were often whipped or even branded, while drunks went into the stocks or pillory” (WJEC). The Elizabethans had what one might call a zero-tolerance attitude to non-conformity. Now, let’s imagine a winsome youth looking out his classroom window at a public flogging as he begins to seriously reconsider flunking those exams. It would be interesting to film Jaques’ reaction to a 2012 Daily Mail (UK) newspaper article which reported that “Growing numbers of teachers are falling victim to serious assaults by young pupils who punch, stab, kick, bite and push.” Incidentally, this refers to pupils as young as 4 years old. Yes, times have changed somewhat, and modern teachers probably need self-defence classes before entering any pedagogical arena. Corporal punishment in UK schools wasn’t banned until 1987, and a cynic might say – if it wasn’t broken then why fix it? The author does not share this prehistoric view and believes instead that children should be fed sugary treats at breakfast and then unleashed on the public school system. What better way to make gladiators of our teaching staff.

Next, the Lover is “sighing like furnace,” which is either a form of heavy breathing or something akin to an adult whining sound. Shakespeare’s idea of love is quite stereotypical. Here is the familiar lovesick youth who burns with passion for an unattainable mistress. The Bard himself was partial to writing some seriously OTT love poems, like Sonnet 18: “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” Interestingly, scholars assert that about two-thirds of Shakespeare’s sonnets are either about, or directly addressed to, a young man. But we shall promptly gloss over this love triangle, ahem, of the Bard, his wife, and the ‘fair youth.’ If one skips forward a few centuries to Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s famous novel – The Sorrows of Young Werther – then one finds the epitome of lovesickness. Werther is a highly sensitive (yet definitely straight) artist who cannot gain the hand of the woman he loves, so he ends up shooting himself in the head – after a few hundred pages of intense self-reflection. It is pertinent to note that dating back in Elizabethan times was quite different to nowadays. Admittedly, “Young people of both sexes in early modern England were fairly free to mix at work and at markets, fairs and dances” (Lyon). However, most marriages at that time were arranged by a young person’s parents or relatives. Free association between the sexes didn’t inspire the same frisson, or maybe it increased the tension since they were likely to be married off to someone else against their wishes anyway. Marriage was all about extending a family’s social network – “The primary purpose of marriage, especially among the upper class, was to transfer property and forge alliances between extended family networks, or kin groups” (Layson and Phillips). Shakespeare is speaking of young men’s love of unattainable women – the approximate equivalent of a modern-day man in a strip club full of Russian beauties whose visas are about to expire. Back in the day, desire and marriage were utterly disconnected, especially for the upper classes. The law was also peculiarly unromantic and resembled more a bond of slavery than love.

“Under the English system of coverture, a woman’s identity was covered by her husband’s when she married. A married couple was regarded by the law as a single entity and that entity followed the will of the husband. Mothers had no legal rights over the guardianship of their children and any property that a woman possessed at the time of marriage came under the husband’s control.”

(Layson and Phillips)

Despite the downfalls of modern dating and marriage, few(er) women end up shackled to a domestic despot who, to add insult to injury, secretly pines for another woman. Shakespeare’s own secret love life would probably require the expertise of Dr. Phil or Esther Perel. Some rumour mongers assert that the mad-about-the-boy sonnets merely reflected the poet’s gratitude to a deep-pocketed, male patron ($$$), but I utterly refuse to contemplate the idea that Mr. S’peare was gay for pay!

The first actual career on the list is that of Soldier. This is somewhat of an anomaly since there was no standing army in England until the year 1660 (some half a century after AYL was written). However, fighting men did need to be recruited during times of social upheaval and foreign wars, and a form of enlistment was sometimes enforced. All men between the ages of 16 and 60 were eligible, but once they were recruited, only one in five would receive any actual training. They were simply issued weapons and expected to learn on the job – so to speak. During the reign of Queen Mary (1553-1558), soldiers’ guns often malfunctioned after being fired just a few times and soldiers were also frequently burned by ignited gunpowder. As a consequence, “many soldiers took to averting their heads while firing, thus missing their targets.” (ISA). Shakespeare aptly writes of soldiers being “Full of strange oaths,” and who would frown upon a vocabulary worthy of a sailor when these fighting men were faced with such atrocious conditions. The Bard also addresses young men’s propensity for testosterone-fuelled shows of courage – “Seeking the bubble reputation / even in the canon’s mouth.” It’s a historical fact that in Elizabethan times, “The untrained, low ranking, disenfranchised common soldier often ended up as cannon fodder” (ISA). In modern times, national armies rely on sophisticated recruitment techniques rather than enlistment. Yes, you’ve probably seen one of those adverts that have been specially crafted to appeal to adrenalin junkies. In some extreme cases, foreign fighters, who are mostly young men, have voluntarily joined the ranks of soldiers in Syria and Ukraine (recent examples). This is doubtless an attempt to show the same calibre of manhood that the poet wrote about so many hundred years ago. It’s strange that it took until the 1960s and the Vietnam War for someone to think of a better motto – Make love, not war.

Much like today, masculinity was held at a premium in Elizabethan times. The description of the soldier being “bearded like the pard” refers to old-school male grooming. Approximately 90% of adult men were sporting some form of beard in the 16th and 17th centuries – “Having a beard was seen as a sign of manliness, whereas being clean-shaven was viewed as a sign of effeminacy, with beardless men usually either young or clerics” (Irvine). One must bear in mind that it was not an era of sophisticated science, so quite understandably, “The Tudors believed facial hair was the result of male sexual heat” (Irvine). Much like today’s urban hipsters, there was a range of styles that could be adopted – “A popular style was a ‘peak de bon‘– a small pointy beard that a lot of Elizabeth I’s courtiers grew” (Irvine). The style specifically referred to by Shakespeare describes whiskers that stick out like a leopard’s. One is unsure which modern dietary supplement would produce such awe-inspiring results. Overall, Shakespeare’s depiction of these bearded soldiers is wonderfully colourful – a cursing hoard with their guns already cocked and pointed in various directions, who probably killed more wildlife than enemies.

Next on Jaques’ list is the Justice. Some misunderstand this to refer to a court judge, but it’s really about Justices of the Peace (JPs) who “were unpaid officials selected by the queen to oversee law and order” (BBC). They had tasks like collecting taxes, arranging for road repairs, and importantly, setting punishments for low-level crimes. There was no police force in England at that time so people were often sentenced to the pillory for various offences. Shakespeare’s description of the Justice is amusing since it conjures up an image of a pot-bellied, Medieval mansplainer – “Full of wise saws and modern instances.” These men were the original brigade of pale, stale males. The “good capon lined” means a neutered rooster who has been specially fattened for the table, quite the delicacy apparently. This bird was commonly used as a bribe with Justices of the Peace.

From the description, the Justice is conspicuously wide in the middle, probably with a shockingly high BMI score, and he is the epitome of middle-aged conservatism. The fat, impotent bird (an aged cock) is also likely a commentary on the men who held such public positions. Even though the Elizabethans didn’t have the little blue pill from Pfizer, the town crier may well have promoted a magic flower called the Saffron Crocus, known “to cause standing of the yard” (French). For those of you unfamiliar with imperial measurements, a yard is 36 inches, so no, they didn’t need television in those days. In closing, the figure of the middle-aged, pill-popping, pompous know-it-all is still to be seen in modern times.

While many commentators divide the life cycle into three stages, Shakespeare gets to a 6th role before we finally meet old age – the “slippered pantaloon.” The moniker means “a foolish old man” (Norton 1649). The name is an allusion to Italian popular comedy of that era. It’s a type of biological farce because the old man begins to shrink at this stage of life. The muscles weaken, along with the voice, and the eyes fail until the world seems smaller and adventures are relegated to mere tales of the past. He has spectacles, which were indeed available in the 15th century. Glasses were first imported from Florence, but they were later produced in London by skilled Dutch immigrants (von Ancken). The hidden subtext here is that only “Professionals such as lawyers, merchants, writers and other members of the literate public were the main consumers of this product” (von Ancken).For most people outside such professions, the world would always have seemed small, regardless of vision problems. Travel in Tudor England still relied on various ancient Roman roads, horses of varying stamina, and going by foot. Only the very well-heeled could afford to explore the continent or further afield. Jaques would doubtless raise an eyebrow at today’s geriatrics who have scuba diving or the Orient Express on their bucket lists. For Elizabethans, the world was always quite small but old age made it shrink even further.

The final stage of the life cycle is “second childishness.” This neatly completes the circle of life with the aged man resembling a baby in his dependency. The life expectancy of the average person in Tudor England was a mere 42 years old so that puts things into perspective. Of course, some people had longer lives. For example, Queen Elizabeth I died at 69 years old. Like the old man who is “Sans teeth”, she too had atrociously bad teeth but feared the pain of actual extractions. In such circumstances, one had to go to “a barber surgeon, the ‘jack of all trades’ of the Middle Ages” (KRiii). These medical practitioners carried out a selection of services such as bloodletting, limb amputations, and pulling out teeth. It’s best to avoid the fancy term of ‘tooth extractions’ here because “Having a tooth removed by a barber surgeon would be done with a pair of pliers and no anaesthetic” (KRiii). On one famous occasion, the queen could only be convinced to have a tooth pulled at a surgeon’s after the Bishop of London allowed one of his own healthy teeth to be pulled as a demonstration that the pain was indeed tolerable. Now, that’s chivalry! Old age was not for sissies in Elizabethan times – even warrior queens were put to the test. Jaques could not possibly imagine a world of elder care including luxurious retirement homes, state pensions, a cornucopia of pain medications, false teeth, and yes, euthanasia. ‘Mummy, I’m taking you to the Dignitas hotel in Switzerland’ would have sounded far more upbeat and adventurous in Shakespeare’s day.

Comparing Jaques’ world to the modern world reveals wider gaps than would be expected. In today’s world, Rosalind would likely be crowned in a Drag King competition, mistaken for a trans man, or accused of conversion therapy due to her unethical procurement of ‘a cure.’ Orlando would be sent for a vision test, or an IQ test, since he can’t recognise his own girlfriend in men’s clothes. Audrey would likely be posting TikTok videos about fashion in her distinctive, regional accent. Almost everything about Shakespeare’s world is difficult to fully comprehend. Platitudes about the Bard’s perfect summation of universal experiences begin to sound quite flaky when one dares to gape into the historical chasm that separates us from Elizabethan times. For one thing, it’s clear that it was a man’s world (James Brown backing track, please). All 7 ages refer to men alone, not mankind, just cis males from the Forest of Arden region (think white wine and white men). There weren’t even any women on the stage, just rouged, prepubescent boys in dresses (honestly). Jacque’s monologue is a famous speech and the disparity between then and now is, for me, one of the most fascinating aspects of it. Having got a better idea of Shakespeare’s world, I’d say vive la différence!

Works Cited.

“A Closer Look at Pregnancy, Midwifery, and breastfeeding in the Tudor Period.” The Folger Shakespeare, http://www.folger.edu/blogs/shakespeare-and-beyond/pregnancy-midwifery-breastfeeding-tudor-period.

“Changes in Crime and Punishment c.1500 to the Present Day.” WJEC CBAC, resource.download.wjec.co.uk/vtc/2020-21/el20-21_7-2-%20kos/eng/methods-punishment-changed-over-time.pdf.

French, Esther. “The Elizabethan Garden: 11 plants Shakespeare would have known well.” The Folger Shakespeare, http://www.folger.edu/blogs/shakespeare-and-beyond/elizabethan-garden-plants-shakespeare.

Irvine, Amy. “Beards and Status in Tudor Times.” HistoryHit, http://www.historyhit.com/beards-and-status-in-tudor-times/#:~:text=For%20the%20Tudors%20and%20Elizabethans,power%20and%20position%20in%20society.

“Join the Army, See the World.” Internet Shakespeare Editions, internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/society/city%20life/soldier2.html

Layson, Hana, and Susan Phillips. “Marriage and Family in Shakespeare’s England.” The Newberry, dcc.newberry.org/?p=14411.

Lyon, Karen. “Wooing and Wedding: Courtship and Marriage in Early Modern England.” The Folger Shakespeare, http://www.folger.edu/blogs/folger-story/wooing-and-wedding-courtship-and-marriage-in-early-modern-england.

Martins, Julia. “Motherhood and Wet Nurses: Breastfeeding in Early Modern Times.” Living History by Dr Julia Martins, juliamartins.co.uk/motherhood-and-wet-nurses-breastfeeding-in-early-modern-times.

“Medieval Dentistry.” King Richard III Visitor Centre, kriii.com/news/2021/medieval-dentistry.

Orwell, George. Nineteen Eighty-Four. Penguin Group, 2012.

“Queen Elizabeth I and government.” BBC Bitesize, www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z88fk7h/revision/6.

Shakespeare, William. “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” Poetry Foundation, http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45087/sonnet-18-shall-i-compare-thee-to-a-summers-day.

Shakespeare, William, et al. The Norton Shakespeare. Third edition. New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 2015.

“Teachers attacked by children as young as Four: Rising tide of violence in Britain’s primary schools.” Mail Online, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2251974/Teachers-attacked-children-young-FOUR-Rising-tide-violence-Britains-primary-schools.html.

“The Life of a Soldier.” Internet Shakespeare Editions, internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/society/city%20life/soldier.html.

Von Ancken, Victoria. “Spectacles.” Medieval London, medievallondon.ace.fordham.edu/exhibits/show/medieval-london-objects/spectacles.

“Warhol Was Right About ’15 Minutes Of Fame.” NPR, http://www.npr.org/2008/10/08/95516647/warhol-was-right-about-15-minutes-of-fame.