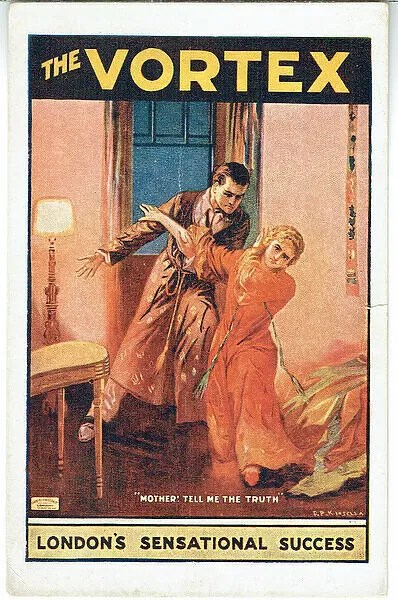

- Play title: The Vortex

- Author: Noel Coward

- Published: 1924

- Page count: 106

Summary

Noel Coward’s The Vortex is a period melodrama that was originally published in 1924. Many of Coward’s later plays are more famous, but this first, major hit was decidedly risqué in its day. The play tells the story of the Lancaster household, which includes Florence the narcissistic matriarch and Nicky her musically talented but confused son. Florence Lancaster dates a string of young, male admirers and that causes scandal due to her married status. In this work, Coward captures the lifestyles of rich, selfish, vain people who attend the theatre and opera, have multiple residences, drink cocktails in the afternoon, and are driven in chauffeured cars. The dramatic events of the play revolve around Nicky’s recent engagement with a girl called Bunty and how this affects his mother’s relationship with her current beau named Tom. The themes of the play include drug abuse, parental responsibility, and homosexuality.

Ways to access the text: reading/listening.

Coward’s play is available online via the Internet Archive under the title “The Vortex: Noel Coward.”

However, if you would prefer to listen to an audiobook version, then one is available on YouTube. The title of the audiobook is “Vortex – Noel Coward – BBC Saturday Night Theatre” and the running time is 1hr and 29mins.

Why read/listen to The Vortex?

1920s Melodrama

Even though melodrama is a term that may be used derogatorily, it also captures the sensational pop of champagne corks and the zing of catty one-liners in this work! Coward’s play evokes a bygone era of English, upper-class privilege, and the author fills each scene with exaggerated characters and thinly veiled taboo subjects. If you like cut-glass accents and witty repartee, then this is the play for you. Admittedly, the work has aged, but this may be viewed in a positive light because the world that Coward describes is practically alien to a modern reader and, therefore, even more entrancing. As an example of Coward’s wit, the character Pawnie is introduced with the innuendo-laden title of “an elderly maiden gentleman.” Pawnie gives embodiment to the overweening vanity and male effeminacy that are core topics in the play. It is possible to encapsulate the overall tone of the play by quoting Pawnie’s succinct description of Nicky – “he’s divinely selfish; all amusing people are.” Coward explores a world of artifice that is shown to be unsustainable because, in the end, the truth shatters everything in a most dramatic manner.

A Neglectful Mother

Florence Lancaster is not the maternal type. She is almost fifty but still feels quite young and is considered attractive by men half her age: men whom she often dates. In modern terms, one could say that she is a liberated woman. However, in the era of 1920s England, her behaviour is considered scandalous and invites widespread gossip. Coward depicts a woman who is unfaithful to her husband but more importantly, in terms of the play’s plot, she is neglectful of her son Nicky. Coward lays the blame on Florence for everything that goes wrong. Florence does not conform to the socially approved gender role of the caring, affectionate mother and she also fails morally. Coward masterfully constructed the entire final scene, which depicts a volcanic confrontation between mother and son, without once naming the core problem. This was due to censorship issues and/or the moral sensitivities of the time. However, the constant side-stepping and dogged refusal to name what Florence is really being accused of, due to her neglect, is ultimately quite fascinating.

Post-reading discussion/interpretation

A Young Man’s Habit

Nicky Lancaster is a drug addict. The initial hints that something is amiss come from his perpetually jittery manner. However, Coward provides Nicky with several masks in the play. The identity that is revealed is frequently not what one expects. To begin, one may consider two of Nicky’s overlapping masks: the neurotic and the drug addict. As Nicky is depicted from the start as slightly neurotic in temperament, it is not immediately evident that he is also a user of hard drugs such as cocaine. For example, the introductory description of Nicky is as a man who “is tall and pale, with thin, nervous hands.” Then, soon after Nicky confesses himself to be “hectic and nervy,” he overreacts to a comment made by Bunty with an unexpected, angry outburst, saying, “Shut up – shut up.” Also, when he plays the wind-up gramophone for his family and friends, he invariably “plays the records too fast.” Even though these are substantial hints at a subtext, it is not until his friend Helen takes a “divine little box” from his pocket when searching for a match that the secret is outed, at least to her. The drug is not named but is most likely cocaine. In a later, private discussion, Helen confronts Nicky by saying, “I should give up drugs if I were you.” Apparently, Nicky’s habit had not gone unnoticed because Helen had suspected it for some time. Yet the salient point here is that the signs need to be read correctly in order to identify the underlying issue. Nicky defends himself against Helen’s warnings, saying, “I only take just the tiniest little bit, once in a blue moon.” The topic is effectively dropped until the final scene when Nicky confesses to his mother by way of showing her the “small gold box,” which Florence recognizes as drugs and then promptly throws it out of the window. The keystone of Coward’s plot is that one problem may easily camouflage another, and not even a mother may know the truth. Masking is a motif in the play.

In terms of a sensational twist to the story, the idea of a young musician returning from Paris with a cocaine habit, especially in the 1920s, is indeed shocking. Yet the revelation does not contribute to the plot in any significant manner except to explain the young man’s pallid looks and generally overwrought demeanour. Drug addiction does not explain why Nicky’s engagement ends abruptly nor does it explain his confrontation with his mother. An inspection of the play’s dialogues confirms these points. Astute audiences may suspect that Nicky uses drugs based on the various early clues, but what about the more frequent hints indicating that Nicky is gay? After all, this topic is never broached. Therefore, one needs to consider what taboos Noel Coward could openly discuss in his work and which needed to remain unspoken. Coward is obviously substituting the taboo that he could tentatively speak of, namely drugs, and leaves Nicky’s homosexuality as an inferred truth. This strange substitution of one taboo for another within the plot leads to an imbalance, an incongruity in the story, unless one deciphers Coward’s full meaning. It is also necessary to digress here and state that what is blatantly clear to a modern audience may have been far more obscure for a 1920s audience. It is crucial for Nicky to make some big revelation in the story, to be truthful about himself, if he is to expect his mother to reciprocally confess her mistakes. It was likely impossible for Coward, both from a censorship aspect and a commercial viewpoint, to have a play’s central character out himself as homosexual in the 1920s. Therefore, drug addiction is used to mimic the shocking confession that is undoubtedly required to bring the narrative to its crisis moment. One theatrical mask obscures another: the confessed drug addict shrouds the hidden homosexual. In moralistic terms, there were many perceived commonalities between drug users and homosexuals in the early 20th century: licentiousness, selfishness, and eventual ruin. The playwright employs a very fitting ruse.

The evidence of Nicky’s homosexuality, like his drug use, is based on shrewd observation. There are numerous early clues such as Nicky’s good friend John Bagot to whom he reads his mother’s letters. This act of sharing displays a level of intimacy between the men. The surname Bagot is also strongly indicative of a derogatory term for gay men (faggot), which was spelt with one ‘g’ in America in the 1920s when Coward himself had visited New York. Noel Coward was a gay man, so he was far more likely to have been familiar with slang terms for the gay community. On the other hand, why would Coward allude to such a derogatory term? Coward’s sly reference to a derogatory term would have functioned as an ironic in-joke for fellow gay men in the audience. The dialogue between Tom and Bunty is the strongest indication that Nicky is gay and that he is perceived as such. For instance, Tom is wholly unaware of the romantic relationship between Nicky and Bunty when he first arrives at the Lancaster household. At one point, Bunty monopolizes Tom in conversation and Nicky unexpectedly storms out, which Bunty explains as jealousy. Tom misconstrues the situation, saying, “Why… is he …?” The inference here is that Nicky is attracted to Tom, and therefore, is a homosexual. This assessment is confirmed by Tom’s further innuendos such as his references to Nicky as “that type” and “that sort of chap” with the closing comment of “you know – up in the air – effeminate.” At precisely this moment, Bunty laughs and says, “I’ve just realized something,” which is apparently that her fiancé is a gay man. When Bunty finally breaks off the relationship with Nicky, she says, “You’re not in love with me, really – you couldn’t be!” Nicky is resigned to the breakup and admits that he is not facing up to things properly: homosexuality is never actually mentioned.

Noel Coward, as a playwright and gay man, had an unenviable challenge in writing The Vortex. In this play, he must commit a form of subterfuge using language in order to explain the problems of gay life. For example, he cannot use any explicit term to denote Nicky’s homosexuality, and yet the playwright’s aim is clearly to convey to readers the kind of perpetual entrapment that gay men felt. Nicky is unable to face the truth of his sexuality when confronted by his fiancé, and he is even unable to fully admit it to himself. One presumes that he would have married Bunty had she not ended the relationship. A major element of Coward’s subterfuge is the technique of psychological projection. By way of illustration, when Nicky is arguing with his mother about her numerous lovers, he says, “It was something you couldn’t help, wasn’t it – something that’s always been the same in you since you were quite, quite young -?” Nicky is evidently referring to himself here and his sexuality. In the next line, Nicky says, “I’m nothing – I’ve grown up all wrong.” Such an admission from Nicky underscores that Coward’s play is more than just a melodrama; it is a play that valiantly struggles to express something that could not legitimately be said publicly at that time. The play expertly depicts Nicky’s utter confusion and resulting self-hatred, yet the playwright was barred from expressing a plain truth in 1920s England – the truth that Nicky is gay.

When the play was written, drug-taking and homosexual practices were both seen as wilfully habitual acts. As such, Nicky’s ruination, in either case, would have been perceived as his own choice. There was, however, a distinct difference between how these two ‘habits’ would have been penalized. The English law covering drugs was the “Dangerous Drugs Act 1920,” which continued to treat substance addiction as a medical problem. On the other hand, the law that covered homosexual practices, namely the “Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885,” meant gay men could face imprisonment for up to two years. This law became known as the “Blackmailer’s Charter” because it put gay men in such a vulnerable position. In the context of the play, Nicky is supported by Helen and later by his mother when he reveals his drug habit. It is not clear how either of these women would have reacted if he had said he was a homosexual. This does not mean that they do not suspect or even know it – the problem is a public admission of homosexuality and the subsequently unavoidable repercussions. Additionally, drug use was considered to be a habit that was curable under medical supervision: homosexuality was not. Coward masks Nicky’s homosexuality, depicting him instead as a drug addict, yet the truth emerges from the playwright’s constant use of ellipses and innuendo. These literal gaps (is he …?) and constant hints (up in the air – effeminate) are what the truth must be constructed from given the restrictions of the era. Ultimately, it is an admission that counts, but Nicky can only safely admit to using drugs but never to the bigger taboo. Coward will not and possibly cannot name the young man’s true habit because it is sexual and therefore guarantees ruin. One can reasonably assert that the playwright’s career would also have been seriously tainted or ended had his play been more explicit. Few plays deliver a message so clearly as Coward’s does, yet simultaneously say nothing at all.

Hamlet’s Mother

Noel Coward’s The Vortex has a climactic final scene where an angry son confronts his mother about her sexual conduct. For many readers, this scene may appear oddly familiar and that is due to its remarkable similarity to a scene from Shakespeare’s Hamlet where the young prince confronts his mother, Queen Gertrude. Both situations are defined by anger that tilts towards outright rage. Nicky says to his mother, “I’m straining every nerve to keep myself under control … if you lie to me and try to evade me any more – I won’t be answerable for what might happen.” Similarly, Hamlet tells Queen Gertrude, “Sit you down; you shall not budge; / You go not till I set you up a glass / Where you may see the inmost part of you,” and the vehemence of his orders make her fear that he will murder her. What is most immediately striking about both scenes is the moral disgust of a son at his mother’s sexual liaisons. In each case, the son looks for and finally gains a promise regarding future behaviour from his mother. Queen Gertrude is induced to feel shame over her hasty marriage to old King Hamlet’s inferior brother Claudius, and she also promises to keep Hamlet’s secret (that he is not mad but very sane and cunning). In Coward’s play, Nicky commands that his mother will not “have any more lovers … you’re going to be my mother for once,” and Florence finally submits, saying, “Yes, yes – I’ll try.” While the two scenes are quite similar, an added connection may be established by reference to Sigmund Freud. It was Freud who diagnosed Hamlet’s Oedipal complex in his book The Interpretation of Dreams, which reveals the young prince’s desire to sleep with his mother. When one considers Coward’s play, it is also a young man’s sexual urges that are in question (Nicky’s). Coward re-creates a scene from Hamlet as a means of exposing what Florence is really being accused of, and that it relates directly to her son’s sexuality.

One may quibble about Coward’s use of such an iconic scene from a great play to make a point in a melodramatic work. Yet the playwright does bring the scene into the 20th century. There is a cocaine-addicted son, apparently homosexual, threatening his mother in her bedroom late at night on the same day that his fiancé has broken up with him. In the case of Hamlet, Freud explains the prince’s prurient thoughts. Hamlet ponders about how his mother lays “in the rank sweat of an enseamed bed.” Freud explains this fascination as evidence of his sexual desire for his mother and his jealousy of her current lover, King Claudius. To explain Nicky’s sexual dilemma, one may extract clues from the similarities between the plays’ scenes. The crucial question in The Vortex comes when Florence asks Nicky, “What are you accusing me of having done?” and his strange answer is “Can’t you see yet! … look at me.” The implication is that Nicky’s ‘problem’ is clear for all to see. This suggests that Nicky cannot hide his sexuality, and there is evidence to support this as Tom and then Bunty have concluded that he is not the marrying type. Coward provides his audience with a well-crafted and content-rich scene between Nicky and his mother. For example, if Nicky’s sexuality can be ‘read’ then surely his mother would have noticed long ago. After all, she is close friends with Pawnie who is depicted as an indiscreet, elderly homosexual. Florence’s ignorance of her son’s sexuality is questionable because when Nicky declares that he has “a slight confession to make” then her response is first to gauge the gravity of it by repeating “confession?” but then she swiftly says, “Go away – go away.” Florence may not want to hear what she already knows. Nicky’s problem, as has already been established, cannot be named, so drug use suffices as the confession. The informative parallel with the Shakespearean scene may be understood as follows – Hamlet obsesses over his mother’s sex life and chastises her, but the secret of the scene is that he is sexually attracted to his mother, whereas Nicky obsesses over his mother’s sex life and chastises her, but the secret of the scene is that he is homosexual and seeks the root cause of his sexual affliction. In both Shakespeare’s and Coward’s dramatic scenes, a young man is being forced to confront a quite taboo element of his sexuality, and in each case, his mother somehow holds the key to the problem.

As Sigmund Freud diagnosed Hamlet’s Oedipal complex then it seems apt to consult the psychologist’s writings once again regarding Nicky. It is true that Freud’s work is outdated to some degree, especially regarding homosexuality, however, it offers an important guide to academic discussions on sexuality around the time Coward wrote The Vortex. In “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality” (1905), Freud makes some helpful observations, for example, he clearly links neuroticism with homosexual feelings. The link between Nicky’s neurotic personality and drugs has already been explored, so it is of interest that Nicky’s neuroticism also hints at his sexuality. Therefore, a characteristic of Nicky that is discussed in the play and is most evident in the climactic scene, is a clue to the sexual subtext. Freud also notes that “inverts [homosexuals] go through in their childhood a phase of very intense but short-lived fixation on the woman (usually on the mother) and after overcoming it they identify themselves with the woman and take themselves as the sexual object.” If one considers Nicky’s idealisation of his mother, then it can indeed be traced back to childhood. Nicky recounts one special memory to Bunty: “I can remember her when I was quite small, coming up to say goodnight to me, looking too perfectly radiant for words.” The intense argument between Nicky and his mother shows that he no longer idealises her, but he once did, and Freud’s theory refers to those important formative years and the crystallization of sexual orientation. The fight between mother and son highlights one specific aspect of Nicky’s sexuality. We are told of how Nicky finally realizes that the gossip about his mother has always been true, and he even witnesses her make a “vulgar disgusting scene” when Tom breaks off the relationship. Nicky, like Hamlet, has been obsessing about his mother’s sexual relations. Therefore, it is not a coincidence that Coward depicts Tom and Nicky as the same age because, consequently, Florence becomes Nicky’s rival in love when it comes to the attention of another male, namely Tom. This links back to Tom’s initial impression of Nicky and the suggestion of sexual jealousy. Just as Hamlet is envious of Claudius’s sexual relations with his mother, Nicky is jealous of his mother’s sexual relations with the “athletic” and masculine Tom.

To explain Nicky’s impulses, one may look to Freud’s book entitled Sexuality and the Psychology of Love. Freud writes of homosexuals, “The typical process … is that a few years after the termination of puberty the young man, who until this time has been strongly fixated on his mother, turns in his course, identifies himself with his mother, and looks about for love-objects in whom he can re-discover himself and whom he wishes to love as his mother loved him.” This point about a boy identifying himself with his mother is peculiar to Coward’s scene between Nicky and Florence since Hamlet identifies instead with his mother’s lover, Claudius. Nicky truly seems to feel that he and his mother are exceptionally alike. His character reflects hers, so he excuses her behaviours, saying – “you’ve wanted love always – passionate love, because you were made like that – it’s not our fault.” The key quote in the play comes when Nicky says of himself and his mother, “We swirl about in a vortex of beastliness.” Their only chance is to accept the truth. However, the truth that Nicky seeks is not a truth that he can express. The closest one gets to naming his sexual ‘problem’ is by way of its apparent causes: his mother’s neglect of her parental duties, her shallow vanity, and her endless string of affairs. In the coded speak of 1920s England, Nicky is blaming his mother for his homosexuality, which means his ruination. Indeed, there is an air of impending doom and disgrace when Nicky references his father and says, “I’m nothing for him to look forward to – but I might have been if it hadn’t been for you [Florence].” Looking forward suggests a career, marriage, and children, but old Mr Lancaster will not see any of these rewards because his son is gay.

The play ends immediately after the dramatic bedroom scene. The resolution that has been agreed upon is that Florence will try to fulfil her, up until now neglected, role of mother. Like Hamlet who was furious at his mother because of his own unspeakable sexual urges, Nicky’s fight with his mother is equally characterized by obvious sexual repression: the inability to accept or even name the true source of the anger. One may highlight a final parallel between the plays. Queen Gertrude promises to keep Hamlet’s secret, and Florence likewise understands her son’s secret and co-operates for that reason. Secrecy is secured through a process of guilt, shaming, and a need for damage control. Coward’s play is an early example of the nature versus nurture debate on same-sex attraction. The playwright’s strong emphasis on ‘nurture’ is clear and was indeed supported at that time by such eminent psychologists as Dr Freud. The play is a snapshot of English society in a quite different era. The parallels between Hamlet and The Vortex reveal the fascinating subtext that Coward creates.

Works Cited

Coward, Noel. The Vortex. Ernest Benn Limited, 1924.

Freud, Sigmund. Sexuality and the Psychology of Love. Collier Books, 1963.

Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. 3rd ed., Seven Treasures Publications, 2008.

Freud, Sigmund. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, David De Angelis, 2018.

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. Penguin Books, 2005.

Teff, H. “Drugs and the Law: The Development of Control.” The Modern Law Review, vol. 35, no. 3, 1972, pp. 225-241.