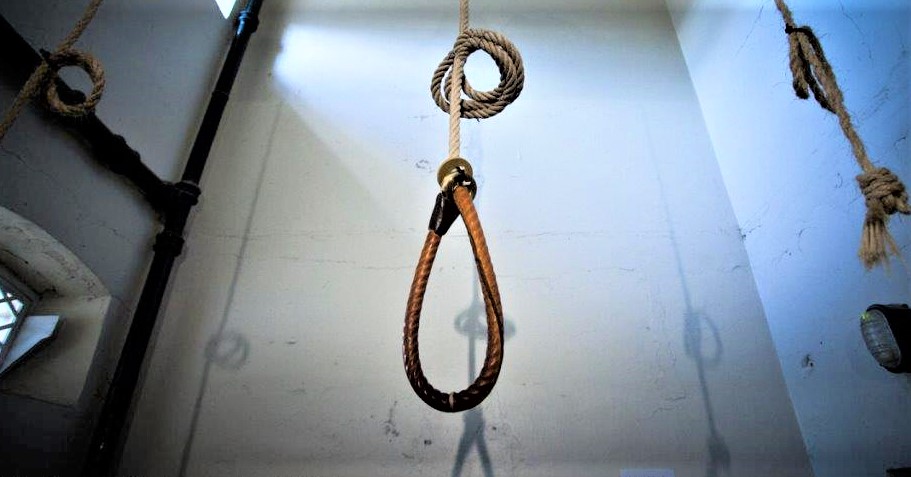

“The Hangman’s Noose” by John Twohig Photography

- Play title: The Quare Fellow

- Author: Brendan Behan

- First performed: 1954

- Page count: 91

Summary

The Quare Fellow is a comedy-drama by Brendan Behan. The play is set in a Dublin prison, and the focus of the work is the planned execution of an inmate called the Quare Fellow. The list of characters for this work is quite extensive but may conveniently be divided into prisoners, prison officials, warders, a few clerics, and the English hangman (plus his assistant). Through the course of three acts, Behan presents prison life from the perspectives of prison newcomers, recidivists, and prison warders. The time span covered is merely twenty-four hours, and events begin with prisoner speculation about a possible reprieve for one of the two death row prisoners. The Quare Fellow is a name that denotes not only that the central character is sentenced to death, but also that his identity is somehow odd and his crimes taboo. Nonetheless, several of the other prisoners describe the horrific details of the murder at the centre of this drama. Behan’s play is widely recognized by critics as being opposed to capital punishment: judicial hangings were still being carried out in Ireland during the 1950s (Russell 73).

Ways to access the text: reading

Behan’s works are generally not easy to source online for free. However, there are copies of several of Behan’s plays, including The Quare Fellow, available through the Open Library (registration is needed, but not payment details). The play is reader-friendly but does contain some Hiberno-English and prison slang, which may not be familiar to all readers.

Unfortunately, there is no audiobook version of this play. The 1962 movie entitled The Quare Fellow is based on Behan’s original play but is an adaptation by Arthur Dreifuss, and the focus of the movie differs from the play.

Why read The Quare Fellow?

Capital punishment

Behan was vehemently opposed to capital punishment (YouTube). The Quare Fellow was certainly influenced by the hanging of a man that Behan knew named Bernard Kirwan who was executed in 1943 (Russell 73). Kirwan’s crime was practically identical to the murder carried out by the fictional Quare Fellow. While some readers may consider capital punishment an anachronistic topic for a play, it is unfortunately still practised in many countries and was obviously in use in Ireland when the play was written. Behan himself served a total of eight years in prison (Russell 75). Therefore, he was intimately familiar with stories of hangings and even some of the victims, and this resulted in a genuinely affecting piece of drama. Importantly, the playwright never reveals the reactions of the condemned man but focuses instead on all those around him. Behan critiques a system in its entirety: the judiciary, government officials, prison workers, prisoners, and even the clerics. The convicted man at the play’s centre remains silent, which symbolizes his utter powerlessness. Within the play, details are provided about hangings that are quite horrifying. Behan impresses upon his audience that society funds such punishments, and he aims to expose the sordid details of a barbaric practice that crucially relies on public support to continue. In short, any system of justice is only as healthy as the society that supports it, and the playwright confronts this rather thorny issue.

Rotten apples

A prison should, in theory, hold characters that are basically rotten apples: some more rotten than others but at least all criminals. However, Behan consciously avoids the kind of binary simplicity that suggests that the high prison walls separate the good in society from those who are feared and justifiably locked away. Readers bear witness to highly subjective views expressed by prisoners and warders alike that serve to further muddy the crystal-clear waters of one’s judgment. Not all the prisoners’ crimes are revealed, but we do learn of a murderer, sex offender, petty criminal, smuggler, and embezzler. Yet, the hierarchy of crimes, especially as judged by the prisoners themselves, leads to some confusion. For example, the two murderers are treated entirely differently both by their fellow prisoners and indeed in judicial terms too, hinting strongly at the influence of class distinctions. Then, the sex offender whose specific crime is never revealed expresses his disgust at being housed amongst murderers. The other prisoners treat him as a pariah. However, the sex offender ironically shows respect for the Holy Bible. The petty criminal called Neighbour is clearly a recidivist but has never done anything worse than steal insignificant amounts of money and alcohol. Behan unexpectedly presents this character, who is most familiar with jail, as arguably the most malign figure of the entire play. The playwright is not rehearsing what is nowadays considered an obvious and tired motto – incarceration becomes a school for criminals. He suggests instead that imprisonment inwardly rots a man’s character, and this is an issue that is weirdly separable from actions such as the original crimes themselves. The playwright presents a nuanced depiction of good and bad that is thought-provoking and sometimes challenging.

Post-reading discussion/interpretation

The Bog-Man Savage — The Native Beast — The Pig

Brendan Behan shows how the trajectory of the Quare Fellow’s story is largely predetermined by the context of the times. This historical context includes the newly independent Irish State and the remnants of an old, English class system. An additional contributory factor to the Quare Fellow’s downfall is the propensity of others to negatively classify him as inferior. The playwright relies heavily on the simile of pig slaughter to make several salient points and crucially to expose the injustice of capital punishment.

The Quare Fellow is depicted in a penitential environment during a specific historical era. To fully appreciate Behan’s critique of the Irish justice system of the 1940s and ’50s requires a reader to have a little background information. In the first place, the playwright himself was imprisoned on two separate occasions for Irish Republican activities (Kao 51). This fact exposes his personal disdain for continuing British involvement in Ireland, specifically Northern Ireland. However, in The Quare Fellow, the playwright also strongly hints that the changes from British rule in Ireland to the Irish Free State (meaning a self-governing Southern Ireland), are merely superficial. For instance, the character Dunlavin says, “The Free State didn’t change anything more than the badge on the [prison] warders’ caps.” It is a historical fact that the Irish State inherited and then largely maintained the former British legal system. Along with inherited laws, there were also the old physical structures such as the prisons. In the first act of the play, we are told that the word “Silence” is written on the prison wall in Victorian lettering. This seemingly innocuous observation conjures up images of an environment shaped by the mindset of a former century. It is also historically accurate, as depicted in the play, that the Irish State always employed an English hangman as it had no executioner of its own (The Irish Times). In these respects, Ireland’s criminal justice and correctional systems could be best described as neo-colonial (Russell 90n34) rather than postcolonial. The examples of laws and prisons show that there was no real sense that British influence had been left behind; on the contrary, it was being sustained by native Irish administrators. This background information does not fully explain yet begins to provide a foundation of understanding about why a “bog barbarian” is executed while another murderer is reprieved in the play. Behan, an ex-prisoner playwright, sets about scrutinizing the system in his own country.

Behan opens an important debate about Ireland’s own post-independence class system. Like most playwrights, he prefers to show rather than explain. He employs a series of interesting mirror effects in the play that serve to question the inevitability of certain outcomes. Take for example how Dunlavin and his friend Neighbour are mirrored by the youthful prisoners Shaybo and Scholara. Will the youths experience the same tragic fate of recurring imprisonment? If not, then what precisely will alter the path upon which they are already firmly set? Then there is the prison system itself: originally operated under British rule but which looks strangely unchanged under Irish rule. A flawed, outdated system will continually lead to flawed outcomes unless there is some intervention. Behan exposes a form of stasis in the system that paralyzes any prospect of improvement. The starkest example of mirroring is that of the two murderers who both await death sentences at the beginning of the play. Why do these mirror-image prisoners experience entirely different outcomes? If young prisoners inevitably become old prisoners, and the prison system is sadly emblematic of times past, then why do expectations change regarding two men on death row? The simple answer is intervention, but this intervention seems to be based solely on the disparate class backgrounds of the two prisoners. Behan inserts an ironic twist in the mirror effect that exposes gross discrepancies in prisoner treatment. If Behan were resolving his drama’s plot, then one could accuse him of employing the literary device of deus ex machina; however, he draws attention to the conspicuousness of the twist of fate thus making it a mystery to be solved.

In The Quare Fellow, class appears to tilt the scales of justice. The man who ultimately receives a reprieve, “beat his wife to death with [a] silver-topped cane” and is therefore known as “Silver-Top.” The cane itself has the ambiguous role of the murder weapon and symbol of a superior class. It was a gift presented to the man from the “Combined Staffs, Excess and Refunds branch of the late Great Southern Railways,” which indicates his former professional career and social standing. Silver Top is said to have a “good accent,” and as Dunlavin humorously comments, “That’s a man that’s a cut above meat choppers.” Even though Silver-Top and the Quare Fellow both murdered a single victim (one killed his wife, the other killed his brother), it is the post-murder events that seemingly differentiate the two men. The Quare Fellow scandalously “cut the corpse up afterwards with a butcher’s knife.” Such barbarity would indeed fuel public outrage and influence the original judicial sentence, but it does not conversely explain why Silver-Top is reprieved. Both men murdered their victims in a barbaric manner. The crux of the problem is certainly exposed with the reprieve of Silver Top. The official reprieve is most unsettling and unsatisfactory to a reader as it is not accompanied by an explanation: it is an act of mercy based on criteria invisible to the public. The courts handed down two separate sentences of death by hanging but only one is overturned. The furore around the butchering of a dead body understandably obscures one’s view of how the justice system should work. The way a murderer disposes of a victim’s body is certainly relevant but surely not of primary concern. Behan’s sympathies lie with the sufferings of the living, not the dead. For example, the playwright purposefully shatters the long-held illusion that hanging delivers an almost instantaneous death. One is subjected to the discomfiting discussion on how long it takes a hanging man to die. One may compare this fate with the fate of Silver Top’s wife who undoubtedly died a cruel death too. Therefore, in summation of this point, the two prisoners on death row mirror one another in practically every feature – except for their class. In this fashion, Behan exposes a definite class inequality. The Quare Fellow is not executed solely on account of his barbarity since his crime is no more barbarous than that of Silver Top. However, the Quare Fellow is from the wrong, i.e., the lower class. The continuing presence of such a prejudiced mindset within the Irish justice system also reflected an age-old English perception of the Irish as savage, untrustworthy, and dangerous. But how could such a mindset persist in a newly independent state?

If subconscious class prejudices exist within the system that Behan depicts, then terminology is a good starting point for an investigation. The derogatory title of “bog-man” is used by prisoners to describe the Quare Fellow, and within this term are echoes of colonial-era, British disdain for the native Irish. The bog stands for everything outside the borders of Dublin’s metropolitan area: the land of the ‘natives,’ and traditionally an area prone to rebellion. The Ireland that Behan describes in the play is not a classless republic but a society still obsessed with class. The prime example is that England is still used as the gold standard by which all things are judged. Prisoner A boasts of having been incarcerated in England as if this were a mark of distinction, and Warder Regan perceptively replies, saying, “There’s the national inferiority complex for you.” Class distinctions also become evident between the prisoners themselves. Prisoner D states that he has a “gold medal in Irish” and is one of “the Cashel Carrolls,” which apparently signify a model Irishman in terms of language skills and genealogy. Yet prisoner D is oddly unable to converse with prisoner C who is a fluent Irish speaker from Co. Kerry, which is in the southwest of the country. One detects a distinct hybrid of Irishness and upper-class superiority in prisoner D. Furthermore, prisoner D has a nephew attending Sandhurst (an English military academy), which suggests that the family may, in fact, be Anglo-Irish: the traditional ruling class in Ireland. Prisoner D also name-drops his influential friends and this supports one’s belief that he moves in powerful social circles. Overall, prisoner D represents conservative, upper-class power in Ireland. He even defends the very penal system in which he is currently incarcerated. To support such a system indicates that it poses no significant threat to him.

Prisoners A and D assert their superiority in several ways including references to England while other prisoners like C and the Quare Fellow are subjected to a negative classification. The most notable term is “bog barbarians.” Dunlavin describes the murder committed by the Quare Fellow as a “real bog-man act.” Prisoners evidently still see themselves as existing within a hierarchy of classes; it is impossible to disassociate this from the residue of English class snobbery in Ireland. The nameless Quare Fellow who comes from the ‘bog’ contrasts with Prisoner D whose identity is founded upon a distinguished family name (the Cashel Carrolls) and possibly an ancient estate too. Behan employs simple terminology to reveal the dividing lines of class that exist even within a prison environment. If classist prejudices persist in such a lowly environment, then it is a problem that riddles all of society.

The converging influences of the state, class system, and devaluing terminology serve to seal the fate of the Quare Fellow. An injustice is revealed in Behan’s play, but the revelation only comes when one comprehends that Silver Top need not die for his heinous crime. It is the reprieve of only one of the death sentences that exposes a stark inequality. Meanwhile, Behan repeatedly confronts us with graphic details of the Quare Fellow’s crime. These details serve to blur our vision of how justice should work. This may seem like a counterproductive tactic by the playwright until one analyses it further. By confronting the gruesome details of the murder, one ultimately gains insight into Behan’s overall message on capital punishment. After all, the main point of the play is the inhumanity of one man taking another’s life: even if it is a judge in a court of law who legitimizes the taking of that life!

Behan depicts a barbarian’s act of murder, or maybe he merely depicts the disposal of a body by the Quare Fellow. The question mark over the murder is reflective of the real-life case of Bernard Kirwan who was sentenced to death based on the discovery of his brother’s butchered corpse (Russell 77n12). As already noted, one never hears the voice of the Quare Fellow so there is never an explanation, admission, or confession. By connecting the murders, one creates a niggle of doubt that is an important introduction to the imagery Behan uses in the play. Behan continually uses the simile of slaughtering a pig to describe the murder itself. This simile provides vital insights into Irish nationality, infighting, class, dehumanization, and greed.

The playwright underlines the Quare Fellow’s identity as Irish as he strives to partially redeem this figure. This is achieved by references to food. The most recognizable and traditional Irish meal is bacon, cabbage, and potatoes. The foundational link between food and the murder is that the Quare Fellow, a native Irish man, “cut[s] his own brother up and butcher[s] him like a pig.” On the day arranged for the Quare Fellow’s execution, he requests two rashers (pig meat) for his last breakfast. One also learns that he “kicked up murder” when a previous day’s request for the same breakfast was impossible because “some hungry pig ate half his breakfast.” These subtle prompts guide one back to the real-life case of Bernard Kirwan who apparently murdered his brother over a dispute involving the family farm (Russell 77n12). Against such a backdrop, terms like getting one’s cut of things, or being allowed to bring home the bacon transform what may seem like a mindless crime into a crime motivated by unfair treatment. The play opens with a prisoner in the isolation cell singing, “A hungry feeling came o’er me stealing,” and one may broaden this sentiment to refer to impoverished, subsistence farmers in rural Ireland like the Kirwan family. Was the Quare Fellow also deprived of what was rightfully his and then retaliated with awful consequences? Do we not witness something similar when a fellow prisoner eats the food from the Quare Fellow’s plate? Behan’s portrayal of the Quare Fellow, as described through prisoner C’s words, is undeniably sympathetic. Prisoner C speaks with the Quare Fellow in the prison yard and later remarks, “I don’t believe he is a bad man.” The playwright creates a sympathetic figure on death row, so that he may challenge the status quo on capital punishment. Behan’s Quare Fellow is not villainous, but he is unquestionably representative of Irishness given his rural background and traditional diet. As such, the simile of pig slaughter reveals, upon first investigation, a counterargument or at least some amelioration of the image of the savage murderer.

One may find critiques of other elements of Irish society in the simile too. As James Joyce once wrote, “Ireland is the old sow that eats her farrow” (221). Behan creates his own twist on this theme of self-destructive, Irish infighting primarily through his depiction of the character of Neighbour. Like the sow that eats its own, Neighbour looks upon the convicted man’s open grave and callously says “We’ll be eating cabbages off that one in a month or two.” The grave of the Quare Fellow will soon become the rich soil of the vegetable garden. The idea of feasting on the misfortune of a fellow prisoner exposes Neighbour’s inhumanity. Neighbour even bets his “Sunday bacon” that the Quare Fellow will be hung, thereby inviting other bets on the event. As noted earlier, Neighbour is the archetype of the rotten apple in prison: the one who is morally corroded and goes on to corrode all those around him. Behan also refers to the next generation of Irish people who will become the ones who feast on others’ misfortunes or are feasted upon. For instance, one learns that Scholara’s girlfriend “had a squealer for him” (a term equally attributable to a child or a piglet). If one accepts that flawed judicial systems and bad personal behaviours are cyclical in nature, then Scholara’s girlfriend is now the mother of one of the next generation’s sacrificial victims. This is in keeping with the overarching theme of slaughter. Behan nimbly alternates between a malign individual like Neighbour who openly seeks to benefit from a man’s death and a new generation of lower-class children who have little hope in life. The playwright exposes a cancer in society; a society where one’s neighbour (in name but not spirit) will look to benefit from his fellow man’s downfall. Like Joyce, Behan’s vision of Ireland is quite pessimistic.

The simile of pig slaughter is a crucial link to the intertwined issues of murder and class. What the Quare Fellow did was truly barbaric. Neighbour describes the crime in graphic detail: “he bled his brother into a crock didn’t he, that had been set aside for the pig slaughtering and mangled the remains beyond all hope of identification.” Even though the dead brother is provocatively compared to a slaughtered pig, Behan is intent on drawing out the comparison so that it is revelatory. For instance, only a ‘beast’ or ‘pig’ could commit such a deed, and this links back to a class hierarchy where the pig refers to someone greedy, dirty, and uncouth: tags that were attached to the Irish well into the 20th century. Is not Behan utilizing this stereotype of the uneducated, savage, bog-man in his portrayal of a murderer? The true intention of the playwright becomes clearer when we witness how the condemned man becomes the one who is sacrificed by the apparatus of the state. Mickser provides a commentary on the hanging: giving details about how they put the “white pudding bag on the head” of the prisoner. White pudding is made of pig meat but without the blood (contrasting with black pudding/blood sausage). This is a covert reference to the original murder, but it is now the murderer who faces a barbaric death. The Quare Fellow is subjected to the same kind of dehumanizing descriptions that one reads of in the original murder. Thus, he is more easily sent to his death. The most chilling, implicit comparison between pig slaughter and the execution is that the other prisoners let out “screeches and roars” at the moment of execution. Such noises mimic the horrendous sounds that a pig would make when slaughtered by traditional methods, namely having its throat cut. Even though this is a bloodless (white pudding) judicial ‘murder,’ it is no less shocking than the black, bloody deed apparently committed by the Quare Fellow. The doubts that linger about the circumstances of the original murder also undermine the belief that justice is being served by hanging the Quare Fellow. It is only when one explores the play in this detailed manner that the true political force of Behan’s condemnation of the death penalty finally becomes clear.

Works Cited.

Behan, Brendan. The Quare Fellow. Grove Press, Inc., 1957.

“Brendan Behan on Capital Punishment.” YouTube, uploaded by jackgrantham1, 24 April 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=urH9xUlK1YU.

Joyce, James. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Penguin Books, 1965.

Kao, Wei H. “Staging the Outcast in Brendan Behan’s Three Prison Dramas.” Journal of Irish Studies, no. 15, 2021, pp. 51-61.

“Last hanging in State 50 years ago today”. The Irish Times, 20 April 2004.

Rankin Russell, Richard. “Brendan Behan’s Lament for Gaelic Ireland: The Quare Fellow.” New Hibernia Review, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2002, pp. 73-93.